In military history, few formations have commanded the awe and respect accorded to the Macedonian phalanx. Perfected by King Philip II of Macedon and wielded with devastating efficiency by his son, Alexander the Great, this infantry formation was central to the Macedonian army’s dominance in the fourth century BC.

The Rise of King Philip II of Macedon

Philip II was the third son of King Amyntas III of Macedon. As a young prince, his prospects of ascending to the throne were initially slim. The pivotal moment in his early life was his time spent as a political hostage in Thebes (c. 368-365 BC), which exposed him to Greek culture, politics, and military tactics. Thebes was a leading military power at the time, and Philip had the opportunity to learn from Epaminondas, a master of Theban tactics and strategy. This experience was instrumental in shaping his understanding of warfare, leadership, and statecraft.

Upon his return to Macedon, Philip found his country in disarray. The kingdom was under threat from neighboring states and internal divisions. His elder brothers, Alexander II and Perdiccas III, reigned successively but were unable to secure the kingdom’s borders or ensure internal stability. After the death of Perdiccas in battle against the Illyrians in 359 BC, the Macedonian throne was left to Perdiccas’ infant son, Amyntas IV. Seeing the vulnerability of his nation and the incapacity of a child king to address these challenges, Philip took the regency and quickly moved to secure his position as king.

Philip’s claim to the throne was contested, but he swiftly and decisively neutralized his opponents through a combination of diplomacy, strategic marriages, and when necessary, force. His initial focus was on stabilizing the kingdom’s internal affairs, restructuring the economy, and reforming the military. He recognized the importance of a strong, loyal army and introduced the Macedonian phalanx, a formation that utilized long pikes to give Macedonian infantry an edge over traditional Greek hoplites.

He built up their morale, and, having improved the organization of his forces and equipped the men suitably with weapons of war, he held constant manoeuvres of the men under arms and competitive drills. Indeed he devised the compact order and the equipment of the phalanx, imitating the close order fighting with overlapping shields of the warriors at Troy, and was the first to organize the Macedonian phalanx.

Diodorus Siculus, c. 90-30 BC

Central to the Macedonian phalanx was a departure from the traditional focus on hoplite warfare, which prioritized the aspis, a heavy shield, as the mainstay of the phalanx. Instead, Philip introduced the sarissa, a long pike about 5 to 7 meters in length. The sarissa significantly extended the reach of Philip’s infantrymen, transforming their combat capabilities. The initial formation of the phalanx was a modest 100-men, ten-by-ten square, comprising mostly inexperienced troops. Sometime before 331 BC, recognizing the need for a more formidable formation, Philip expanded the phalanx to a 256-men, sixteen-by-sixteen square, further enhancing its offensive and defensive capabilities.

Weaponry: Sarissa, Xiphos, and Pelte

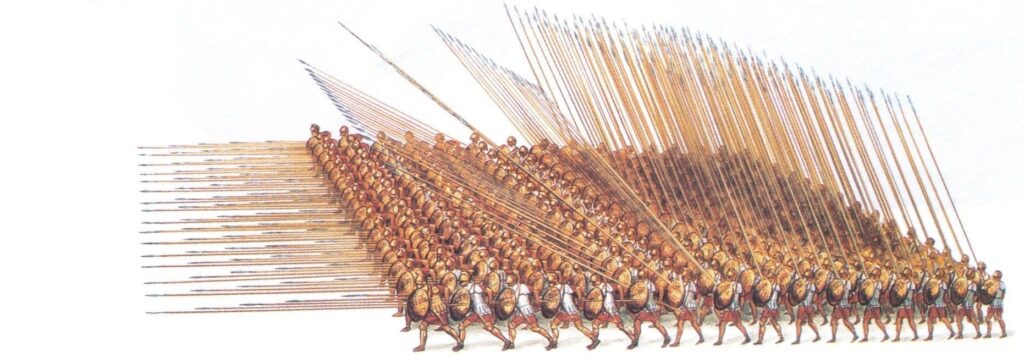

Constructed in two pieces for ease of transport, the sarissa was assembled before battle, creating a long and formidable weapon that extended far beyond the front lines of the phalanx. This design allowed the first five rows of phalangites to project their sarissae beyond the formation’s front, creating a dense thicket of spear points that could impale multiple enemies at once. The length of the sarissa meant that opponents were kept at a distance, where the tightly packed formation of the phalanx could best utilize its offensive capabilities. For enemies attempting to close in, the multitude of spear points presented an almost impenetrable barrier.

Understanding the vulnerability of the phalanx to projectile attacks, the soldiers positioned beyond the first five rows would angle their sarissae at approximately a 45-degree angle. This tactic was intended to create an overhead barrier to deflect or intercept incoming arrows and other projectiles, providing an additional layer of protection for the formation.

In close combat situations where the sarissa was less effective, the phalangites relied on a secondary weapon: the xiphos, a short sword designed for stabbing and slashing at close range. This weapon ensured that phalangites were not defenseless should enemies breach the sarissa’s reach.

The shield carried by each phalangite, known as a pelte, was smaller and lighter than the traditional Greek aspis. Measuring about 24 inches in diameter and weighing around 12 pounds, the pelte was made of bronze-plated wood. It was worn hung around the neck by a strap, allowing the soldier to wield the sarissa with both hands. The design of the pelte contributed significantly to the mobility and flexibility of the phalanx.

Armor: Kranos, Linothorax, and Knemides

Phalangites wore helmets (kranos) made from bronze or iron. The design of the helmets varied, with some resembling the traditional Greek Corinthian helmet, which covered the entire face but had slits for the eyes and mouth. Over time, the design evolved to offer better visibility and hearing, crucial for coordination in phalanx formations. The Chalcidian, Thracian, and pilos helmet types became popular among Macedonian phalangites for these reasons, featuring wide brims and open faces.

The body armor worn by phalangites was typically a linen cuirass, known as a linothorax, which was made from multiple layers of linen glued together. This material choice provided a good balance between protection and mobility. The linothorax was lightweight compared to bronze cuirasses, allowing soldiers to move more freely without sacrificing too much protection. Some phalangites may have also worn bronze cuirasses, but these were likely less common due to their weight and cost. Additionally, phalangites often wore greaves to protect their lower legs. Known as knemides, the greaves were usually made of bronze and fitted to the shape of the leg, offering protection against cuts and blows to this vulnerable area.

The combined weight of the armor and weaponry carried by a phalangite was approximately 40 pounds, nearly ten pounds lighter than the equipment burden of a traditional Greek hoplite. This reduction in weight allowed the phalangites to maintain greater endurance and maneuverability on the battlefield, despite the heavy load of the sarissa.

Formation

Central to the phalanx’s organizational structure were the syntagmata, battalion-sized blocks that constituted the phalanx’s primary units. Each syntagma was organized into sixteen files (width), each file also numbering sixteen men (depth), resulting in a total of 256 soldiers per syntagma. This square formation allowed for the effective use of the sarissa, with the first five rows of pikes projecting forward to form a formidable wall of points against the enemy.

The overall command of a syntagma was held by a syntagmatarch, who, along with his subordinate officers, would position themselves in the first row of the block. This placement allowed them to lead directly from the front, an essential factor in maintaining order and direction during the chaos of battle.

Leadership within each file was entrusted to a dekadarch, one of the most experienced Macedonian soldiers, who received approximately triple the pay of an ordinary phalangite. The dekadarch was supported by two veteran soldiers positioned behind him and another veteran soldier at the very end of the file. These positions were critical for maintaining coherence and direction within the files, especially during movement and combat. The veterans were compensated with double pay, reflecting their crucial role and experience.

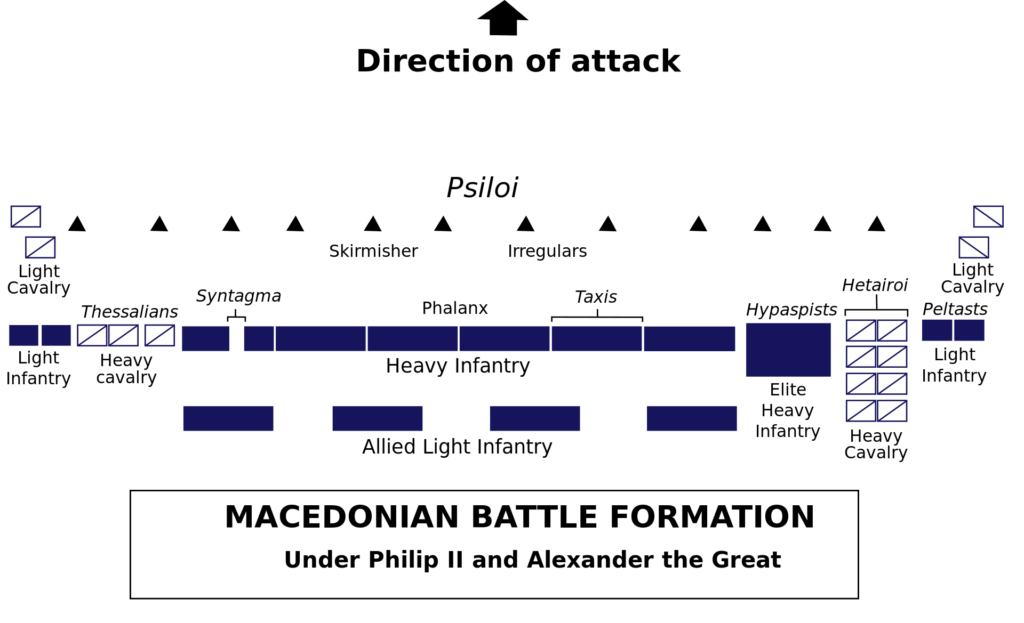

Multiple syntagmata formed a larger unit called a taxis, which could vary in size but typically consisted of 1,024 men (or four syntagmata). The taxis was commanded by a chiliarch. A full Macedonian phalanx could include several taxeis, with the exact number varying depending on the size of the army and the specific requirements of a campaign. The entire phalanx was under the command of a strategos or a general, with Philip or Alexander serving as the supreme commander in most significant engagements.

Tactical Use

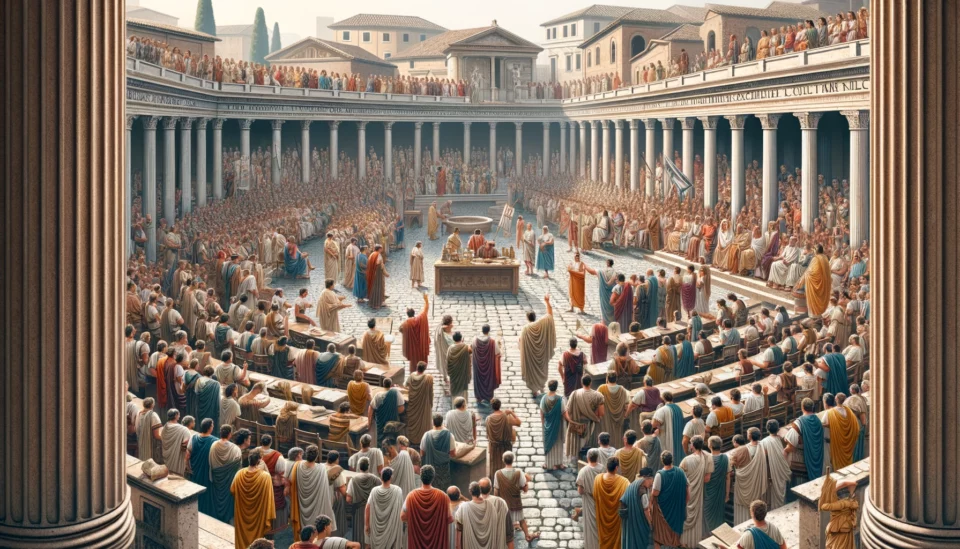

The phalanx’s tactical use under Philip was characterized by its role as the main striking force in battle, supported by cavalry and light infantry to protect its flanks and exploit enemy vulnerabilities. The phalanx was typically deployed in the center of the battlefield, where its dense formation and long spears could exert maximum pressure on the enemy lines. The objective was to break through the enemy’s infantry, creating chaos and disarray into which cavalry and other forces could charge.

One of Philip’s favored tactics, later perfected by Alexander, involved using the phalanx as an ‘anvil’ against which enemies were pressed. Then, using his cavalry as the ‘hammer’, he would strike the flanks or rear of the enemy forces, effectively crushing them between the two forces.

Alexander’s greatest tactical innovation was the integration of the phalanx into a broader combined arms strategy. He used light infantry and archers to screen the phalanx and protect its vulnerable flanks, while his elite cavalry, led often by himself, was held in reserve to exploit openings or strike at the enemy’s weak points. Alexander frequently used the phalanx in oblique formations, advancing one wing more aggressively to draw the enemy into an unfavorable engagement. This would be combined with cavalry or light infantry attacks on the flanks or rear, enveloping the enemy in a deadly pincer movement.

In many battles, such as Gaugamela in 331 BC, Alexander used the phalanx not as the primary breakthrough force but as a holding entity that engaged the main body of the enemy. This allowed him to use his cavalry to execute decisive maneuvers, such as flanking attacks or charges against enemy leaders. The phalanx’s strength lay in its ability to maintain cohesion and present an unbreakable front to the enemy. However, this same strength was also its Achilles’ heel. The formation’s rigidity made it vulnerable to uneven terrain and flank attacks. Its reliance on close order meant that any disruption could quickly lead to disarray and defeat. Alexander’s genius lay in his ability to mitigate these weaknesses through tactical flexibility and the integration of various arms in his army.

Legacy

The Macedonian phalanx’s effectiveness declined after Alexander’s death, as his successors, the Diadochi, faced enemies who developed counter-tactics. The Roman legions, with their more flexible manipular formations, eventually proved superior. Nonetheless, the phalanx left a lasting legacy in military history. It demonstrated the power of innovation in warfare and the importance of combining different arms and tactics. The image of the phalanx, advancing with its forest of sarissae, remains one of the most enduring symbols of Alexander’s military brilliance and the ancient Macedonian empire’s might.