The Battle of Artemisium, fought in the summer of 480 BC during the Greco-Persian Wars, occurred simultaneously with its land-based counterpart, the legendary Battle of Thermopylae, and was pivotal for the subsequent Greek victories in this conflict. The clash between the Greek coalition and the superior Persian navy unfolded over a period of three days.

Seeds of Conflict: A Brewing War

The origins of the conflict trace back to the Ionian Revolt between 499 BC and 493 BC, a major uprising by the Ionian Greek cities of Asia Minor against Persian rule. Dissatisfaction with the tyrants appointed by the Persians and the heavy tax burdens imposed led to this significant, though ultimately unsuccessful rebellion. Athens and Eretria supported the Ionians by sending ships and troops to assist in their struggle, a gesture that set the stage for the ensuing Persian response.

The suppression of the Ionian Revolt and the subsequent sacking of Miletus in 494 BC by the Persians under King Darius I were followed by a desire to punish Athens and Eretria for their support of the rebellion. This led to the First Persian Invasion of Greece in 492 BC, a punitive expedition that sought to extend Persian control over the Aegean and subjugate the troublesome Greeks once and for all. The campaign culminated in the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC, where the Persians were decisively defeated by a smaller Athenian force.

The decade following the Battle of Marathon was a period of preparation and anticipation. Both sides knew that the conflict was far from over. The Persians, keen on avenging their defeat and completing the conquest of Greece, embarked on an ambitious project of military expansion and preparation. Simultaneously, the Greeks, aware of the Persian threat, began to forge alliances and prepare their defenses. This period saw the formation of an unprecedented coalition of Greek city-states led by Sparta and Athens, who put aside their differences and formed a defensive alliance dedicated to the common cause of defending Greece from Persian aggression.

King Xerxes I, son and successor of the late Darius, launched the Second Persian Invasion of Greece in 480 BC. The Persian army advanced through the Hellespont, constructing a massive pontoon bridge across it, and moved through Thrace and Macedonia, subjugating the regions and securing their line of advance toward Greece. Meanwhile, the Persian navy sailed down the coastline, headed for the island of Sciathos. With an army estimated to number between 120,000 and 300,000 troops, and a vast navy of around 1,200 ships, Xerxes had the overwhelming numerical advantage. The Greeks, in stark contrast, possessed a considerably smaller fleet of around 280 ships, all of them waiting for the Persian armada to appear at the Straits of Artemisium.

Strategy: The Two-Pronged Defense

The choice of Artemisium as the theater of naval operations was no accident. This location, nestled in the narrow straits off the coast of Euboea, was chosen for its strategic confluence with the simultaneous land battle at Thermopylae. The narrowness of the Straits of Artemisium mirrored the terrestrial chokepoint of Thermopylae, where a small contingent of Greek hoplites, led by King Leonidas I of Sparta, aimed to hold back the Persian land forces. Similarly, at sea, the confined waters restricted the maneuverability of the larger Persian fleet, mitigating their numerical advantage and allowing the agile Greek triremes to exploit their tactical advantages in ramming and boarding actions.

The Greeks, under the strategic guidance of Eurybiades and Themistocles, adopted a defensive posture that leveraged these geographical constraints to their advantage. Understanding that a head-on confrontation with the entire Persian armada would spell certain doom, the Greek strategy was to lure portions of the Persian fleet into the straits where their numbers would be less overwhelming, and their inability to effectively maneuver could be exploited. This approach required not only a deep understanding of naval tactics but also an unparalleled level of coordination between the Greek city-states, whose naval contingents had to operate as a single, cohesive unit despite their diverse origins.

The strategic interplay between the battles of Artemisium and Thermopylae was a stroke of Greek strategic insight. By holding both chokepoints, the Greeks aimed to simultaneously stall the Persian advance by land and sea, buying precious time for the preparation of further defenses and the evacuation of vulnerable regions. The battles were conceived as two fronts of the same war, where success in one arena could bolster morale and strategic positioning in the other. The Greeks understood that neither battle would be a decisive victory. However, by holding the line at both locations, they aimed to inflict maximum damage on the Persians, drain their resources, and potentially force them to reconsider their invasion plans. Artemisium and Thermopylae were calculated gambles, desperate attempts to buy time and set the stage for a more decisive victory later in the war.

Catastrophic Losses: A Violent Storm

In a dramatic twist of fate, and before the Persian and Greek fleets were anywhere near each other, a substantial portion of the Persian fleet suffered catastrophic losses due to a violent storm off the coast of Magnesia, near the mountainous region of Mount Pelion. This event unfolded as the Persian armada navigated the treacherous waters along the Thessalian coast. The storm, described by ancient historians as an act of divine intervention favoring the Greeks, raged with ferocious intensity, catching the Persian navy off guard. The tempest’s force was such that it wreaked havoc on the Persian ships, which were not only laden with troops but also with supplies critical for the planned land operations against the Greek city-states. Estimates of the losses vary, but it is widely acknowledged that the storm led to the sinking of approximately 400 of the Persian ships, drowning thousands of sailors and soldiers, and severely depleting the supplies intended for Xerxes’ campaign.

The Persian fleet put to sea and reached the beach of the Magnesian land, between the city of Casthanaea and the headland of Sepia. The first ships to arrive moored close to land, with the others after them at anchor; since the beach was not large, they lay at anchor in rows eight ships deep out into the sea. They spent the night in this way, but at dawn a storm descended upon them out of a clear and windless sky, and the sea began to boil. A strong east wind blew, which the people living in those parts call Hellespontian. Those who felt the wind rising or had proper mooring dragged their ships up on shore ahead of the storm and so survived with their ships. The wind did, however, carry those ships caught out in the open sea against the rocks called the Ovens at Pelion or onto the beach. Some ships were wrecked on the Sepian headland, others were cast ashore at the city of Meliboea or at Casthanaea. The storm was indeed unbearable. They say that at the very least no fewer than 400 ships were destroyed in this labor, along with innumerable men and abundant wealth.

Herodotus, c. 484-425 BC

Opposing Forces: The Persian and Greek Fleets

Persian Fleet

According to ancient sources, notably Herodotus, the Persian fleet that assembled for the invasion of Greece was an impressive amalgamation of forces from across the vast Persian Empire. The exact number of ships that made up the Persian fleet is subject to historical debate, with estimates ranging widely from 600 to over 1,200 ships. Significant contributions come from Phoenicia and Egypt, both renowned for their seafaring and shipbuilding capabilities. The Phoenicians, in particular, were considered the premier sailors and naval architects of the ancient world, and their large contingent reflects the strategic importance Xerxes placed on Phoenician expertise in naval warfare.

For the purpose of providing a detailed overview, we will utilize Herodotus’ account, which suggests a fleet of 1,207 warships, supported by a considerable number of transport and supply vessels. Herodotus provides the following breakdown of the contingents that comprised the Persian fleet. It is however important to note that his account is about the Persian fleet that assembled at Doriskos in the spring of 480 BC, which is before one-third of the ships were lost because of the storm off the coast of Magnesia. According to Herodotus’ calculations, this left the Persian fleet with about 800 ships by the time it reached Artemisium.

| Region | Number of Ships |

|---|---|

| Phoenicia and Syria | 300 |

| Egypt | 200 |

| Cyprus | 150 |

| Cilicia | 100 |

| Ionia | 100 |

| Pontus | 100 |

| Caria | 70 |

| Aeolia | 60 |

| Lycia | 50 |

| Pamphylia | 30 |

| Dorians (Asia Minor) | 30 |

| Cyclades | 17 |

| Total | 1,207 |

Greek Fleet

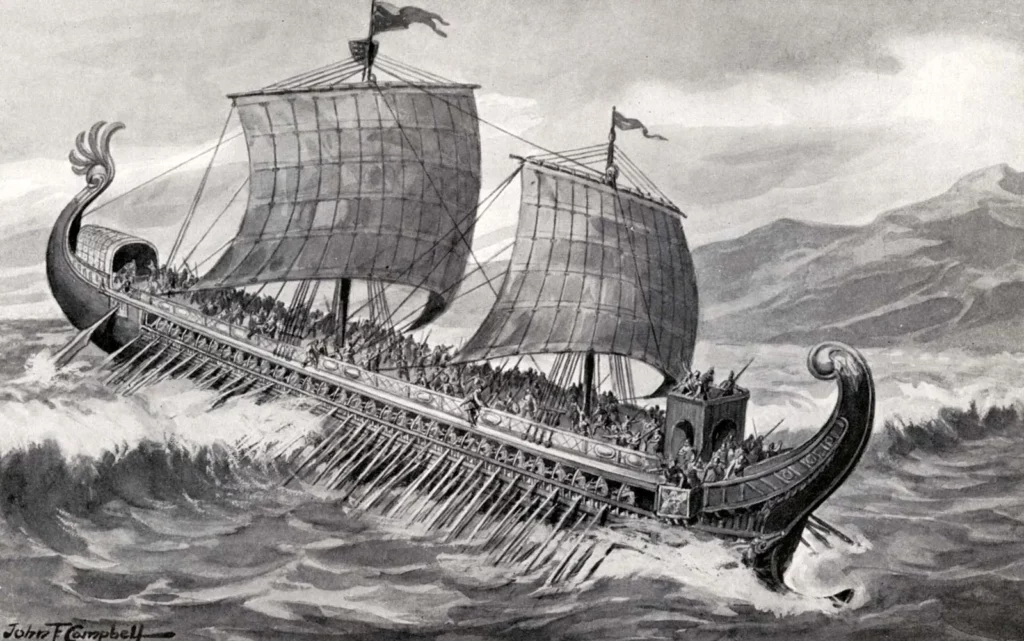

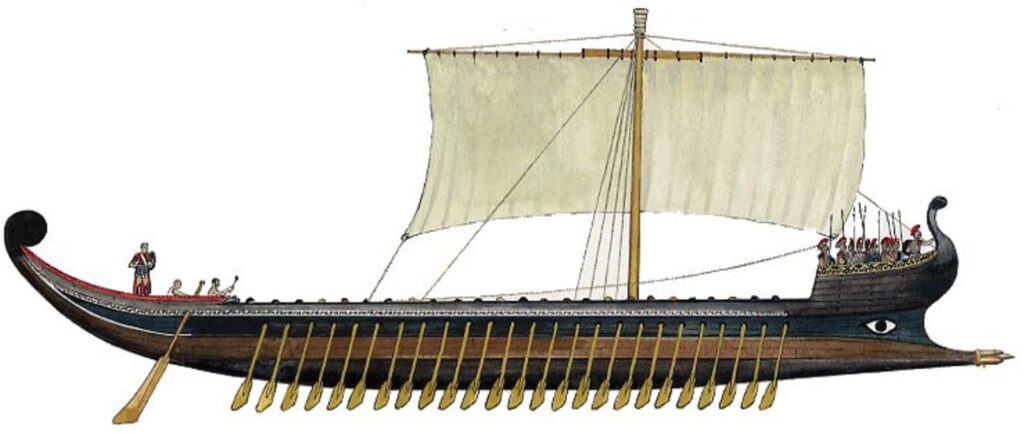

The Greek fleet that assembled to face the Persians was a remarkable coalition of naval power from across the varied city-states of Greece. This fleet, primarily composed of triremes, the state-of-the-art warship of the ancient Mediterranean, numbered around 280 vessels. Triremes were sleek, fast, and highly maneuverable ships, powered by three tiers of oarsmen on each side, and were equipped with a bronze battering ram at the prow, designed to puncture the hulls of enemy ships. A small portion of the Greek fleet was made up of penteconters, predating the triremes and characterized by their long, narrow hulls and single rows of oars. The penteconter’s single row of oarsmen meant that it had a relatively lower profile in the water, reducing its visibility and making it suitable for surprise attacks or rapid coastal raids.

The largest contingent of the fleet was provided by Athens, which, understanding the critical nature of the naval conflict, contributed an impressive 127 triremes. The Spartan contribution was modest, reflecting their traditionally land-oriented military focus. For a detailed recount of the composition of the Greek fleet at Artemisium, we again refer to Herodotus, who provides the following breakdown of the naval contingents.

| City-State | Number of Ships |

|---|---|

| Athens | 127 |

| Corinth | 40 |

| Chalcis | 20 |

| Megara | 20 |

| Aegina | 18 |

| Sicyon | 12 |

| Sparta | 10 |

| Epidaurus | 8 |

| Eretria | 7 |

| Opuntian Locris | (7) |

| Troezen | 5 |

| Ceos | 2 (2) |

| Styra | 2 |

| Total | 271 (9) |

Three Days of Battle

First Day

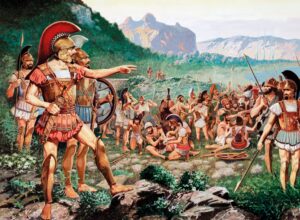

The Persians, noticing the Greek fleet moving towards them late in the first day, decided to seize what they perceived as a golden opportunity to attack. Their decision was likely influenced by their numerical superiority and confidence in their seamanship. The Persians expected a swift and decisive victory over the smaller Greek fleet, quickly advancing to engage in battle. Contrary to their expectations, the Greeks had a strategy in place for such an encounter. They maneuvered their ships to form a defensive formation, with the bows facing outward and the sterns gathered together at the center.

While the exact shape of this formation is debated, whether it was a circle, as inferred from Thucydides’s account of later naval battles, or a crescent to prevent the Persians from encircling them, the intent was clear: to neutralize the Persian advantage in seamanship and perhaps counter specific Persian tactics like the diekplous (a maneuver to break through enemy lines). The complexity of forming such a formation, especially with the large number of ships involved, suggests that the Greeks likely adopted a more practical crescent shape. This formation was designed to counter the Persians’ maneuverability and tactical options.

Upon executing this formation and then launching a sudden counterattack at a second signal, the Greek forces took the Persian fleet by surprise. The Persians, finding their seamanship and tactical advantages negated, suffered significant losses, with 30 of their ships either captured or sunk. During the battle, a Persian ship even defected to the allied side. The first engagement concluded at nightfall, with the Greeks emerging in a better position than they might have anticipated.

During this first day of the battle, a critical piece of intelligence had reached the Greek forces. A deserter from the Persian fleet, known as Scyllias, told the Greek commanders that the Persian command had detached a contingent of 200 seaworthy ships, ordering them to sail around the outer coast of Euboea. The objective of this detachment was to encircle the Greek fleet and trap it against the main Persian force and the coastline, cutting off any potential Greek retreat or reinforcement, and forcing them into a disadvantaged engagement where the Persians could exploit their superior numbers.

Another storm prevented the Greeks from setting off southwards to counter the Persian detachment sent around the outside of Euboea. This same storm, however, proved disastrous for that same detachment, driving them onto the rocky coast of the Hollows of Euboea and causing significant losses, eliminating the threat of the Greeks being trapped between Persian lines.

Second Day

On the second day of the Battle of Artemisium, coinciding with the second day of the Battle of Thermopylae, the Persian fleet found itself in a state of recovery. The back-to-back storms had inflicted significant damage on the Persian ships, compelling them to focus on repairs rather than offensive actions. The Greek forces received two pieces of crucial information that day: first, news of the Persian shipwreck off Euboea’s coast reached them, likely boosting the Greek morale. Second, they received a significant reinforcement of 53 ships from Athens, bolstering their numbers and capabilities.

Seizing the initiative later that day, the Greeks launched an attack against a patrol of Cilician ships, part of the Persian naval contingent. This assault, executed in the late afternoon, perhaps to utilize the element of surprise or to avoid a prolonged engagement that could extend into the night, resulted in the destruction of these Cilician ships. Historians suggest two possibilities for the presence of these Cilician ships: they might have been survivors from the previously wrecked Persian detachment that attempted to navigate around Euboea, or they were possibly stationed in an isolated harbor, making them vulnerable to a targeted attack.

Third Day

On the third day of the battle, the scene was set for a decisive confrontation between the Persian fleet, now fully rallied and prepared for an all-out attack, and the Greek forces, determined yet outnumbered. As dawn broke, the Persians meticulously formed their ships into a semicircle, aiming to envelop the Greeks in a tactical pincer movement. In response, the Greeks attempted to fortify their blockage of the straits, readying themselves for the imminent clash. The tension in the air was palpable as the Persians advanced, triggering the Greeks to row forth boldly into battle.

The conflict that ensued was intense and grueling, lasting the entirety of the day. The Greeks, facing the sheer might of the Persian armada, were stretched to their limits in an effort to maintain their defensive line. Amidst the chaos, the heavily armored Egyptian contingent on the Persian side distinguished themselves, engaging in fierce combat with the Greek hoplites and capturing five Greek ships. On the Greek side, the Athenians shone brightly as the day’s most formidable combatants, with Clinias, the son of Alcibiades, notably contributing a ship and two hundred men at his own expense. The battle ultimately saw both fleets sustaining roughly equal losses as they disengaged at nightfall. For the smaller Greek fleet, however, the toll was disproportionately heavy, with half of the Athenian ships either damaged or lost.

In the aftermath, as the Greeks regrouped at Artemisium, the reality of their precarious situation dawned upon them. The heavy losses sustained made it clear that maintaining their position would be untenable in the face of another Persian assault. The arrival of Abronichus with grim tidings of the Greek defeat at Thermopylae underscored the futility of holding Artemisium any longer. With no strategic advantage to be gained and their forces significantly diminished, the difficult decision was made to evacuate immediately.

As the Greek fleet sailed to Salamis to assist with the final stages of the evacuation of Athens, Themistocles executed a plan aimed at weakening the Persian naval forces from within. His targets were the Ionian Greeks, who, despite their Greek heritage, were serving in the Persian navy, largely due to the Persian Empire’s conquest of Ionia. Themistocles left inscriptions at water sources along the route that the Persian fleet was likely to use. These inscriptions were specifically addressed to the Ionian Greek sailors within the Persian fleet, appealing to their ethnic and cultural ties to Greece. The messages urged them to defect to the Greek side, or at least refrain from actively participating in the upcoming battles.

Themistocles, however, picked out the seaworthiest Athenian ships and made his way to the places where drinking water could be found. Here he engraved on the rocks words which the Ionians read on the next day when they came to Artemisium. This was what the writing said: “Men of Ionia, you do wrongly to fight against the land of your fathers and bring slavery upon Hellas. It would best for you to join yourselves to us, but if that should be impossible for you, then at least now withdraw from the war, and entreat the Carians to do the same as you. If neither of these things may be and you are fast bound by such constraint that you cannot rebel, yet we ask you not to use your full strength in the day of battle. Remember that you are our sons and that our quarrel with the barbarian was of your making in the beginning.” To my thinking Themistocles wrote this with a double intent, namely that if the king knew nothing of the writing, it might induce the Ionians to change sides and join with the Greeks, while if the writing were maliciously reported to Xerxes, he might thereby be led to mistrust the Ionians and keep them out of the sea-fights.

Herodotus, c. 484-425 BC

Aftermath: Salamis, Plataea, and Mycale

The Persians were alerted to the Greek withdrawal by a boat from Histiaea. Initially skeptical, they dispatched reconnaissance ships to Artemisium, confirming the absence of the Greek fleet. Their subsequent actions, sailing to Histiaea and devastating the surrounding area, demonstrate a strategy aimed at punishing those perceived as enemies or traitors.

The aftermath of Artemisium and Thermopylae saw the Persian land-based forces, unopposed, ravaging the Boeotian cities of Plataea and Thespiae, and advancing towards an evacuated Athens. Meanwhile, the Greeks fortified the Isthmus of Corinth, effectively creating a physical barrier to Persian advance into the Peloponnese. However, Themistocles advocated for a more aggressive strategy than mere defense. By simultaneously drawing the Persian navy into the confining Straits of Salamis, the Greeks orchestrated a masterful naval victory, devastating the Persian fleet and thereby neutralizing the immediate threat to the Peloponnese.

The Persian response to these setbacks was a strategic withdrawal by Xerxes, who, fearing an attack on his bridge across the Hellespont and the potential entrapment of his forces in Europe, retreated to Asia with the bulk of his army. He left Mardonius in charge of continuing the Persian campaign, a decision that would lead to the subsequent Battle of Plataea. Here, the Greeks, united in purpose, would achieve a decisive victory against the Persians, effectively halting the Persian invasion. Simultaneous with the Battle of Plataea, the naval Battle of Mycale further crippled Persian naval power, ensuring the security of the Greek mainland from future seaborne invasions. These victories at Plataea and Mycale marked the end of the Persion invasion of Greece.

Conclusion

The Battle of Artemisium stands as a testament to the resilience and strategic acumen of the ancient Greeks in the face of overwhelming Persian aggression. This naval conflict, contemporaneous with the legendary Battle of Thermopylae, showcased the importance of intelligence, geographical knowledge, and naval skill. Despite being outnumbered, the Greek fleet, under the leadership of Eurybiades and Themistocles, managed to inflict considerable damage on the Persian navy, leveraging their superior understanding of the local maritime conditions.

The engagement at Artemisium was not just a battle. It was a critical holding action that allowed the Greek forces to prepare for further encounters against the Persians, particularly the decisive Battle of Salamis that followed. The Greeks’ ability to unite against a common enemy, despite their usual internecine conflicts, marked a pivotal moment in ancient history, emphasizing the value of collective defense against tyranny.

Although the battle did not result in a clear victor, its outcomes had far-reaching implications. It demonstrated the effectiveness of Greek naval tactics and highlighted the strategic significance of the Greek navy. Moreover, the battle underscored the psychological component of warfare, with Themistocles’ cunning inscriptions addressed to the Ionian Greek sailors within the Persian fleet.