In the summer of 480 BC, the Battle of Thermopylae saw a small coalition of Greek city-states face off against the vast invasion force of the Persian Empire. At a narrow pass between the mountains and the sea, the Greeks delayed the much larger Persian forces. Simultaneously, the Greek navy moved to block the Persian fleet at the Straits of Artemisium, intending to prevent them from flanking the land forces at Thermopylae by sea.

Prelude to the Battle: The Ionian Revolt

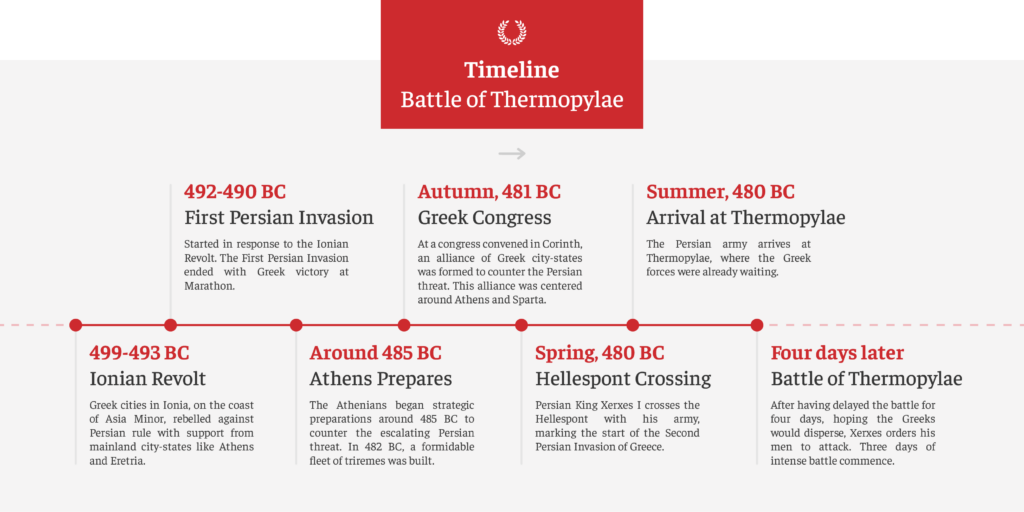

Decades before the battle, rising tensions between the expanding Persian Empire and the fiercely independent Greek city-states set the stage for conflict. Starting with Cyrus the Great, the Persian kings expanded their empire across Asia Minor, incorporating a variety of peoples and cultures. King Darius I expanded Persian territories to the borders of the Greek mainland, heightening tensions that eventually led to the Ionian Revolt between 499 BC and 493 BC. With support from mainland city-states like Athens and Eretria, Greek cities in Ionia, on the coast of Asia Minor, rebelled against Persian rule. Although the revolt was quashed, it significantly angered King Darius and shifted his focus to the Greek mainland.

Motivated by a desire to punish Athens and Eretria for their support of the Ionian Revolt, Darius initiated the First Persian Invasion of Greece. This invasion comprised two distinct campaigns between 492 BC and 490 BC. Led by Mardonius, Darius’ son-in-law and a Persian general, the initial campaign had two aims. It sought to reintegrate Thrace and extend Persian control into Macedon. The campaign began with a show of naval strength and the subjugation of islands of the Aegean Sea. After that, Mardonius led his forces overland and successfully reconquered Thrace. As the Persian army advanced, it successfully compelled Macedon to become a fully subordinate part of the Persian Empire, expanding Darius’ influence in the Balkans. However, the campaign was marred by logistical problems and a major setback occurred when much of the Persian fleet was destroyed by a storm off Mount Athos. The storm’s damage and an attack by the Thracian tribe of Brygi, which wounded Mardonius, forced the Persians to retreat, ending the initial campaign.

Two years later, Darius launched a second expedition. Now the goal was to directly punish Athens and Eretria for their roles in the Ionian Revolt. Commanded by Datis and Artaphernes, the Persian force, with infantry and cavalry aboard about 600 ships, sailed across the Aegean Sea and captured several Cycladic islands before arriving at Euboea. After besieging Eretria for six days, the Persians razed it and enslaved its inhabitants. Following this, they made for Attica, landing at the Bay of Marathon. The Athenians, bolstered by a small contingent from Plataea, engaged the Persians in the Battle of Marathon. Under the military leadership of Miltiades, who employed the famous Greek phalanx formation, the Greeks managed to envelop the Persian lines, leading to a decisive victory despite being outnumbered. The demoralized and beaten Persian forces retreated to Asia after their defeat, marking the end of the First Persian Invasion of Greece.

Darius was determined to avenge the humiliation of Marathon and secure his empire’s western territories by launching an even more extensive and well-prepared invasion. Motivated by the desire to subdue Greece completely, Darius began massive preparations for what would be known as the Second Persian Invasion of Greece. However, his plans were interrupted by his death in 486 BC. The late king was succeeded by his son, Xerxes I, who inherited both the Persian throne and his father’s resolve to conquer Greece. Xerxes spent the first few years of his reign quelling revolts in Egypt and Babylon, which reaffirmed his control over the empire and allowed him to redirect resources toward the Greek campaign. Xerxes oversaw the construction of a pontoon bridge across the Hellespont and the digging of the ‘Xerxes Canal’ through the Isthmus of Mount Athos. The canal was dug to avoid the dangerous circumnavigation that had resulted in the loss of many ships during Mardonius’ initial campaign of the First Persian Invasion.

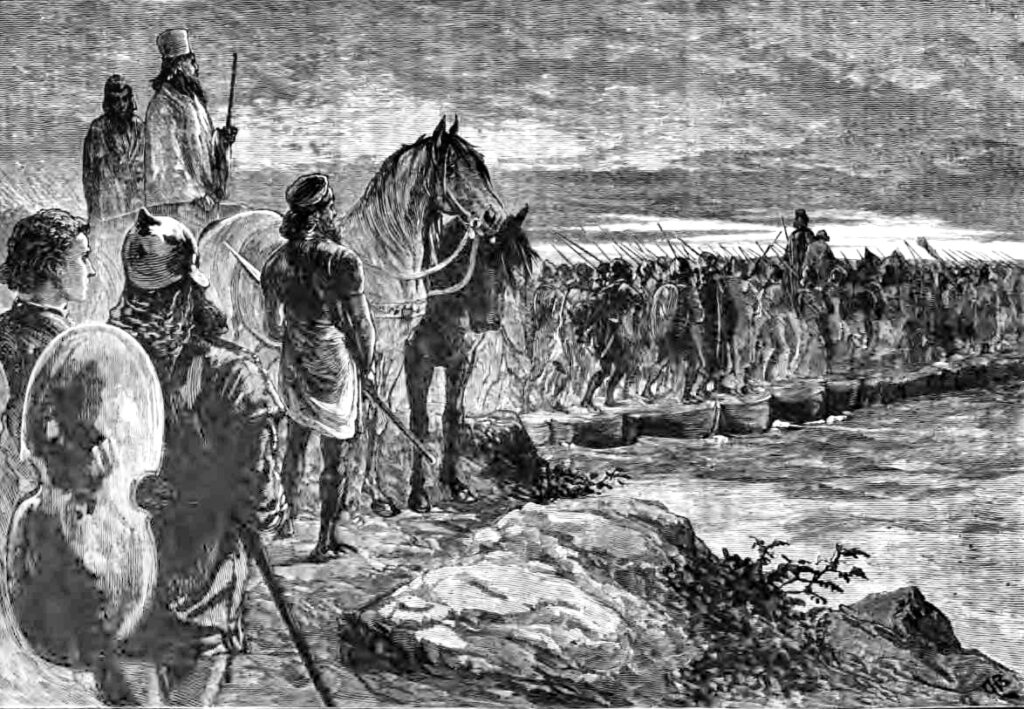

By 480 BC, Xerxes was ready to resume his father’s mission. He assembled an enormous army and navy, reportedly larger than any force ever amassed in the ancient world. Herodotus famously claimed that the army numbered over two million, a figure now regarded by historians as an exaggeration. Regardless, it was an impressively large force designed to crush the Greek city-states once and for all.

The Greek Alliance: An Uncommon Display of Unity

With conflict looming, the Athenians began strategic preparations around 485 BC to counter the escalating Persian threat. Under the guidance of Themistocles, an Athenian politician and general, the decision was made in 482 BC to build a formidable fleet of triremes. This fleet would serve as the backbone of resistance against the Persian navy. However, the Athenians were acutely aware of their insufficient manpower to confront the Persians on both land and sea. Thus, they sought reinforcements from other Greek city-states, heralding a need for a unified Greek defense.

In 481 BC, Xerxes sent ambassadors to various Greek city-states requesting ‘earth and water’ as tokens of their submission. Athens and Sparta were deliberately excluded from these overtures, an omission that galvanized further support around them. A congress convened in Corinth in late autumn of that year, marking a seminal moment in Greek unity. There, a confederate alliance of Greek city-states was formed, de facto led by Athens and Sparta. The formation of this congress was a remarkable feat given the typically fractious nature of inter-city relations. At the time, some members were even at war with each other. Upon joint counsel, the confederate alliance had the authority to send envoys to request assistance and to deploy forces to strategic locations.

When the congress reconvened in the spring of 480 BC, a Thessalian proposal was brought forth. Thessaly, a region in northern Greece, was particularly vulnerable to invasion due to its geographical location. The Thessalian leaders, aware of the impending threat, proposed that the Greek forces should assemble at the Vale of Tempe. This valley, located on the border between Thessaly and Macedon, was a strategic pass that provided a direct route southward through which Xerxes’ army was expected to march. Acting on the Thessalian proposal, the congress decided to send a force of 10,000 heavily armored hoplites to defend the valley.

Upon arriving at the Vale of Tempe, the Greek commanders soon reassessed their strategy. King Alexander I of Macedon, whose kingdom was already under Persian influence, informed the Greek commanders that the Persian army was vastly superior not only in numbers but also in the resources at its disposal. More critically, he pointed out that the Vale of Tempe could be bypassed through the Sarantoporo Pass. This meant that even if the Greeks held the valley, the Persians could easily maneuver around them, rendering the defense ineffective and potentially encircling them. Recognizing the validity of Alexander’s intelligence and the tactical disadvantage of their position, the Greek commanders ordered a retreat. Shortly after, they received news that Xerxes and his army had indeed crossed the Hellespont, moving from Asia into Europe and beginning their march toward Greece.

With the Persian crossing of the Hellespont and the apparent futility of defending the Vale of Tempe, Themistocles proposed a new strategy: using both the narrow pass of Thermopylae and the Straits of Artemisium as choke points. These locations would counteract the Persians’ numerical advantage. Heeding his advice, the congress adopted this two-pronged approach. Themistocles’ strategy was not merely defensive but also included preemptive measures to safeguard the wider Greek civilization. In case Thermopylae and Artemisium would fall, the next line of defense would be the Isthmus of Corinth. This narrow strip of land connecting the Peloponnese to the mainland could be fortified easily, creating another defensive barrier. Themistocles also planned for the safety of Athenian civilians, understanding that Athens was especially vulnerable to Persian attack. He orchestrated their evacuation to Troezen, a city in the Peloponnese, ensuring that they would be safe from immediate harm and preserving the future of Athens regardless of the city’s fate.

Strategy: The Two-Pronged Defense

Following Themistocles’ proposal, the Greek strategy focused on holding the pass of Thermopylae on land and the Straits of Artemisium at sea. Both locations were crucial in guarding the approach to central and southern Greece, forming the core of the Greek defense. Holding both Thermopylae and Artemisium, the Greeks aimed to delay the Persian advance, buying time to organize further defenses and seek additional support from other Greek city-states. The locations were strategically chosen for their terrain, which limited the deployment of large forces and helped neutralize the Persian numerical advantage.

Thermopylae, known as the ‘Hot Gates’ due to its nearby sulphur springs, is a narrow pass between the mountains of central Greece and the sea. In ancient times, the pass was much narrower than today, possibly no more than a few meters wide at its narrowest point, making it an ideal defensive position for the Greeks, as their hoplite phalanx could effectively block the advance of the Persian forces. The hoplites, armed with long spears and protected by heavy bronze armor and shields, formed a wall of spears and shields that was nearly impenetrable in such confined quarters. The narrowness of the pass meant that the Persian army, despite its vast numbers, could only attack in small, manageable groups. This negated their numerical advantage and allowed the Greeks, under the command of King Leonidas I of Sparta, to hold their ground effectively.

The Straits of Artemisium, a narrow channel between the northern coast of the island of Euboea and the Greek mainland, presented a similar bottleneck at sea. This channel forced the Persian navy into a narrower formation, diminishing their ability to outflank or surround the smaller Greek fleet. The Battle of Artemisium aimed to protect the flank of the forces at Thermopylae and stop the Persian navy from encircling and isolating the Greek army by landing troops behind their lines.

Meanwhile, Xerxes intended to use the overwhelming numbers of the Persian army and navy to defeat the smaller Greek forces. This strategy was reflective of Persian military doctrine which often relied on the use of overwhelming force to subdue opponents, a tactic that had proved effective in the vast expanses of the Persian Empire. The Persian strategy at Thermopylae initially involved frontal assaults on the Greek position. Xerxes believed that the sheer number of his forces could simply overwhelm the Greeks through attrition.

Among the Persian forces were the Immortals, an elite unit named for their practice of always maintaining their strength at exactly 10,000 men. Whenever a member was killed or wounded, he was immediately replaced, thus the unit’s number remained ‘immortal.’ This corps was heavily armored and trained for decisive engagements, and Xerxes relied on them to break the Greek lines if the initial waves of infantry charges were not able to do so.

A significant psychological aspect underpinned the Persian strategy. Xerxes aimed to demoralize the Greek defenders by showcasing his vast forces and their relentless attacks. The Persians used the sight of their vast army and the sound of thousands of troops as tools of fear. The hope was that the Greeks, seeing the endless waves of Persian soldiers, would lose heart and disperse.

The Oracle of Delphi: A Grim Message

Before the battle, the Spartans sought guidance from the Oracle of Delphi. The oracle was considered the most important divination center in the Greek world. Leaders and individuals from all over Greece and beyond would seek the guidance of the Pythia, the priestess at Delphi, who was believed to channel prophecies directly from the god Apollo. The message the Spartans received was both worrying and mysterious. Herodotus records that the Pythia predicted that either a Spartan king had to fall or Sparta itself would be wasted by the Persians.

When the Spartans asked the oracle about this war when it broke out, the Pythia had foretold that either Lacedaemon (the city-state of Sparta) would be destroyed by the barbarians (the Persians) or their king would be killed. She gave them this answer in hexameter verses running as follows: “For you, inhabitants of wide-wayed Sparta, Either your great and glorious city must be wasted by Persian men, Or if not that, then the bound of Lacedaemon must mourn a dead king, from Heracles’ line.”

Herodotus, c. 484-425 BC

Sparta was unique in having two kings simultaneously, one from each of the two royal houses of Agiad and Eurypontid. The existence of two kings allowed Sparta more flexibility in military campaigns, as one king could lead the army into battle while the other managed affairs at home. King Leonidas I, who came from the Agiad family, was one of the reigning kings during the time of Xerxes’ invasion. In the context of the dire predictions from the Oracle of Delphi combined with Leonidas’ role as the military commander of the Greek forces, it was presumed that he was the king whose fall would serve to protect Sparta from destruction.

Intending to comply with the oracle’s prophecy, Leonidas is said to only have selected troops who had living sons. This emphasizes that the Spartan king was consciously preparing for a suicide mission. By choosing soldiers with sons, Leonidas ensured that each fallen warrior would leave behind an heir, and therefore the sacrifice at Thermopylae would not be the end of their families’ honor or contribution to Spartan society.

Opposing Forces: The Persian and Greek Armies

Persian Army

Herodotus’ accounts suggest that Xerxes mobilized an immense force of 2,641,610 military personnel for the Second Persian Invasion of Greece, with an equal number of support staff, suggesting a total of over five million people. This number, however, is often viewed skeptically by modern scholars as an exaggeration meant to underscore the drama and the heroic scale of the Greek resistance.

Modern historians have proposed much smaller numbers, generally ranging from 120,000 to 300,000 soldiers. This range is based on realistic assessments of the logistical capabilities of the time, including the limits on how many troops could be effectively fed, armed, transported, and managed. These scholars consider factors such as the supply lines required to sustain such a force over great distances, the capacity for ancient logistical support, and the proportion of the population that could realistically have been mobilized for military service without causing severe disruptions to essential societal functions like agriculture.

The implications of these estimates extend to the specifics of Thermopylae. The actual number of Persian troops present at the battle remains uncertain, as not all forces would have been engaged at the pass. Some of Xerxes’ troops were likely left as garrisons in locations like Macedon and Thessaly. What is clear, however, is that the Persian army significantly outnumbered the Greek forces present at Thermopylae.

Greek Army

On the Greek side, the forces assembled were much smaller but highly trained and motivated. The Spartans, under Leonidas, were professional soldiers, raised from childhood for warfare and regarded as among the finest warriors of the ancient world. Accompanying the Spartans were Thespians, Thebans, and several thousand other Greeks from various city-states, including hoplites from Corinth and Arcadia.

The historical accounts regarding the composition and size of the Greek army at Thermopylae vary significantly between sources, creating a complex puzzle for historians. Herodotus and Diodorus Siculus provide different figures, which are then interpreted and adjusted by modern historians to attempt to reach a more accurate estimate. Herodotus reports that the Greek force at Thermopylae was comprised of several contingents from various city-states. He notes the presence of helots (servants and state-owned serfs of the Spartans), who were possibly armed retainers, but he does not specify their number in the battle context.

| Region | Number of Troops – Herodotus |

|---|---|

| Sparta – hoplites | 300 |

| Sparta – helots | Unknown |

| Tegea | 500 |

| Mantineia | 500 |

| Arcadia – Orchomenos | 120 |

| Arcadia – other areas | 1,000 |

| Corinth | 400 |

| Phleious | 200 |

| Mycenae | 80 |

| Thespiai | 700 |

| Thebes | 400 |

| Opuntian Locris | “All they had” |

| Phocis | 1,000 |

| Total | 5,200 plus the Spartan helots and Opuntian Locrians |

Diodorus Siculus provides a slightly different composition, suggesting 1,000 Lacedaemonians (which may or may not include the 300 Spartan hoplites) and higher numbers for other Peloponnesian groups. Additionally, Diodorus mentions forces not specified by Herodotus, like the Malians and Opuntian Locrians.

| Region | Number of Troops – Diodorus Siculus |

|---|---|

| Sparta – hoplites | 300 |

| Sparta – other | 700 or 1,000 |

| Other Peloponnesians | 3,000 |

| Malis | 1,000 |

| Thebes | 400 |

| Opuntian Locris | 1,000 |

| Phocis | 1,000 |

| Total | 7,400 or 7,700 |

Modern historians generally regard Herodotus as more reliable but still approach his figures with caution due to possible exaggerations or errors in transmission over time. By adding Diodorus Siculus’ 1,000 Lacedaemonians and an average of 900 helots to Herodotus’ count of 5,200, they estimate a total of around 7,100 Greek defenders, not counting the other additional numbers from Diodorus Siculus’ account or any Opuntian Locrians.

The Battle Unfolds: Betrayal Looms

First Day

Upon reaching the pass of Thermopylae, Xerxes was advised of the relatively small Greek force holding the position led by King Leonidas of Sparta. Surprised by the audacity of such a small force blocking his path, Xerxes chose to delay the attack for four days. This delay has been interpreted in several ways: as a tactic to demoralize the Greeks through his display of patience and overwhelming force, or possibly, as some historians suggest, Xerxes was waiting in expectation that the Greeks would disperse upon realizing the futility of their resistance against his superior numbers.

On the fifth day, after the period of delay, Xerxes finally ordered his troops to attack, expecting a quick defeat of the Greek forces. He first attempted a long-distance engagement. He ordered 5,000 archers to launch a barrage of arrows towards the Greek positions. However, this effort proved largely ineffective. Modern scholars estimate that the archers were positioned at least 100 yards away, a distance at which their arrows could not penetrate the Greek defenses. The Greeks were well-protected by their aspis shields, which were large and round, sometimes covered with a thin layer of bronze, and complemented by bronze helmets. These defenses effectively deflected the Persian arrows, causing minimal damage to the Greek forces.

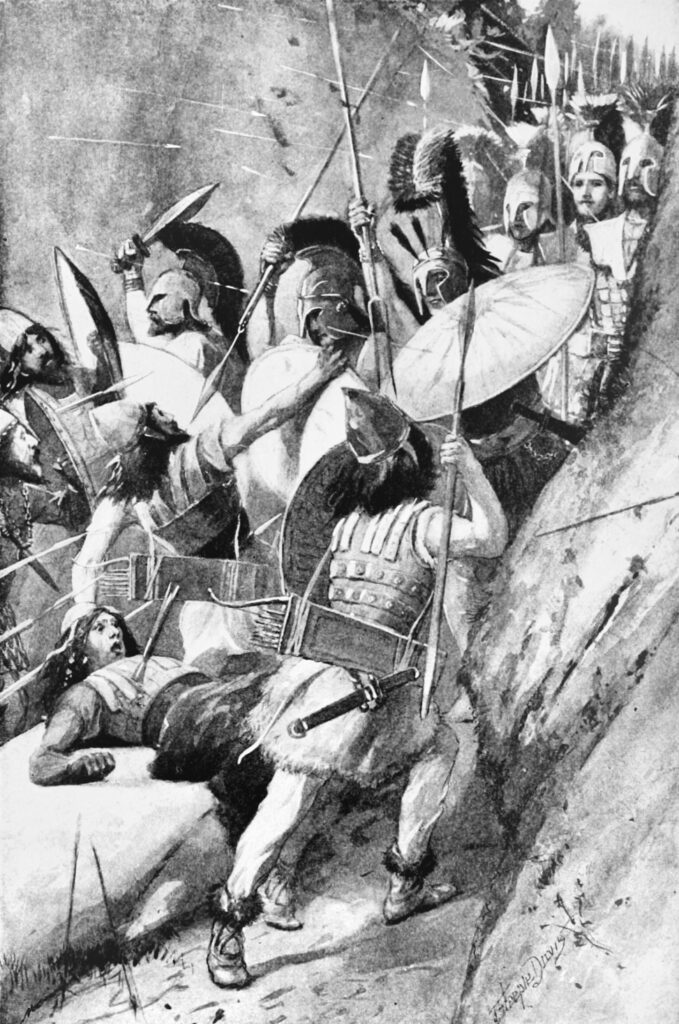

Following the unsuccessful archery assault, Xerxes sent in his Median and Kissian troops, who were expected to sweep aside the defenders with little trouble. Leonidas and his forces positioned themselves in front of the Phocian Wall at the narrowest part of the Thermopylae pass. This location was strategically chosen because it restricted the number of Persian troops that could attack at once. The Greek soldiers formed a phalanx, a tight formation where they stood shoulder to shoulder, presenting a wall of overlapping shields with spears protruding outward. This formation was ideal for the narrow pass and was highly effective as long as it spanned the width of the pass, preventing the Persians from outflanking them and forcing them to make frontal assaults against this formidable defensive setup.

The Persians, wielding lighter shields and shorter weapons, struggled to break through the Greek phalanx. Their equipment was not suited for the type of close, heavy combat that the phalanx formation was designed to combat. Throughout the day, the Medes and Kissians threw themselves against the Greek phalanx but were repeatedly repelled with heavy casualties.

Frustrated by the lack of progress and the unexpected resistance, Xerxes withdrew his troops and sent in the Immortals, his elite guard, towards the end of the day. Despite their fearsome reputation and superior training, they too found themselves stifled by the narrow pass and the disciplined Greek phalanx, suffering severe losses as the Greeks, rotating their troops to keep them fresh, maintained their defensive posture. According to reports, the Greek forces employed a tactical feint: pretending to retreat to draw the Persians forward and then turning quickly to strike the overextended enemy. This maneuver further devastated the Persian morale and inflicted heavy losses.

The first day of battle ended with significant Persian casualties and no real progress in breaking through the Greek defenses. The failure of the Immortals to make a decisive impact shook the confidence of the Persian army and boosted the morale of the Greek defenders. Themistocles’ strategy to use the geography of Thermopylae to neutralize the Persian numbers and King Leonidas’ ability to maintain the cohesion and morale of his troops set the stage for the subsequent days of fighting.

Second Day

On the second day, the Persian king commanded his infantry to attack the Greek position again, expecting that the wear and tear of combat had diminished the Greeks’ ability to defend the pass effectively. However, despite the fresh efforts of the Persian troops, they were met with the same staunch resistance as on the first day. The phalanx formation of the Greeks remained unyielding, with soldiers rotating efficiently to manage fatigue and injuries, thus maintaining their defensive integrity. Xerxes, observing the ineffectiveness of his troops against the stubborn Greek defense, was confounded and dismayed. He withdrew his forces and retreated to his camp, deeply perplexed and uncertain about how to proceed.

As Xerxes was contemplating his next move, he was approached by a local Greek from Trachis named Ephialtes, who saw an opportunity to gain a reward by betraying the Greek defenders. Ephialtes informed Xerxes of a lesser-known mountain path that circumvented the pass of Thermopylae. Starting from the east of the Persian encampment, the path traversed the ridge of Mount Anopaea, which lay behind the cliffs flanking the Thermopylae pass. The path then branched in two directions, one leading towards Phocis, an area north of the Gulf of Corinth, and the other descending towards the Malian Gulf at Alpenus, the first town of Locris. This latter path gave the Persian forces a route to encircle and come upon the Greeks from behind, completely bypassing the natural defenses of the narrow pass at Thermopylae. Motivated by the prospect of a reward, Ephialtes offered to guide the Persian army along the mountain path.

The king was at a loss about how to deal with this impasse, but just then Ephialtes of Malis, son of Eurydemos, came to speak with him, expecting to win some great reward for telling the king of the path that led through the mountain to Thermopylae. By so doing, he caused the destruction of the Hellenes (the Greeks) stationed there. Xerxes was pleased and exhilarated by what Ephialtes promised to accomplish, and he at once sent off Hydarnes and those under his command, who set out from camp at the time the lamps were being lit.

Herodotus, c. 484-425 BC

Leonidas knew about the mountain path since the locals of Trachis, a city close to the battlefield, had informed him of the route’s existence. A few days earlier, he had deployed a force of 1,000 Phocians to guard the path. The Phocians were likely chosen due to their familiarity with the terrain, being from the nearby region of Phocis. The Spartan king tasked them with the responsibility of holding the heights along the path, essentially to act as an early warning system and to prevent any Persian forces from passing through undetected and reaching the rear of the Greek troops.

On the evening of the second day of battle, Xerxes deployed Hydarnes the Younger, one of his trusted commanders, to lead the critical flanking maneuver along the mountain path, guided by Ephialtes. Hydarnes was in command of the Immortals, but it is likely that, given the casualties suffered by the Immortals during the initial day of battle, his force was augmented with additional troops to ensure it reached the full strength required for such a crucial task. Diodorus Siculus indicates that Hydarnes commanded a force of 20,000 men for this mission, implying a significant reinforcement beyond the standard complement of the Immortals.

Third Day

Megistias, a seer accompanying the Greek forces, first told the Greeks that death was coming to them. He did so after examining the sacrificial offerings, an ancient practice where the entrails of animals were inspected to divine the will of the gods. Further confirming the prophecy, deserters from the Persian side came during the night and informed the Greeks of the Persian troops’ circuitous route to flank them. Additionally, watchers stationed on the heights came down at dawn with reports that verified the movements of Persian forces approaching from the rear.

Meanwhile, the Phocians tasked with guarding the mountain path detected the approaching Persian forces, not by seeing them, but by the rustling of oak leaves caused by the march of Hydarnes’ troops. The sudden realization of the Persian approach surprised both parties: the Phocians were not prepared for an engagement, and Hydarnes was momentarily taken aback, fearing he had encountered Spartan troops. Upon learning from Ephialtes that they were ‘only’ Phocians, he decided against engaging them in a prolonged fight, choosing instead to focus on the primary objective of encircling the main Greek force. After a brief confrontation in which the Persians fired a volley of arrows at the Phocians, who had retreated to a nearby hill to make a stand, Hydarnes moved his troops quickly past them, continuing towards the rear of the Greek position.

Faced with overwhelming evidence of their impending encirclement and likely defeat, the Greek commanders convened to discuss their course of action. Herodotus notes that their opinions were divided. Some argued for holding their position, committed to the strategy of defending the pass at all costs. Others, assessing the same set of facts, advised retreat to save their forces for future engagements where they might stand a better chance. The inevitability of defeat at Thermopylae, once the Persians managed to flank their position, made withdrawal a reasonable option to preserve their strength for subsequent battles.

Ultimately, many of the Greeks left Thermopylae, dispersing to their respective cities to prepare for the defense there. A core group remained, including the 300 Spartans, 400 Thebans, and 700 Thespians, all led by Leonidas. The situation of the Theban contingent at Thermopylae has been a subject of historical debate. Herodotus suggests that the Thebans were essentially hostages, ensuring the loyalty of Thebes, a city with questionable allegiance. Contrarily, Plutarch implies that if they were truly hostages, they would have been dismissed with the other Greek contingents. The narrative that these were loyalist Thebans, opposed to Persian rule, suggests they were at Thermopylae by choice, facing certain death or the impossibility of returning home should the Persians dominate Boeotia. The Thespians, led by general Demophilus, decidedly chose to remain voluntarily, expressing a firm resolve to stand and die alongside the Spartans.

Herodotus suggests that Leonidas consciously ordered many of the Greek contingents to leave Thermopylae, and he offers two possible reasons for the Spartan king’s actions. First, he suggests the king might have been concerned for the safety of the allies, knowing well that defeat was imminent due to the Persian forces managing to outflank them. Sending away the majority of the allies would prevent unnecessary slaughter and allow these forces to fight another day. However, Herodotus himself favors a second explanation, focusing on the Spartan ethos. He speculates that Leonidas recognized the faltering morale among the allies, who were disheartened and unwilling to face certain death. In contrast, the Spartans, raised from birth to value martial glory and heroic sacrifice, were culturally and psychologically prepared for such an end. By dismissing the dispirited allies, Leonidas could maintain the battle readiness and moral integrity of his force, ensuring that those who remained were fully committed to the cause.

The Spartan king’s decision to remain at Thermopylae is often viewed through the lens of the prophecy from the Oracle of Delphi: by choosing to stay and die, Leonidas secured the future of the Spartan city-state. His decision was also a strategic move. By holding the narrow pass with his remaining hoplites, Leonidas prevented the Persian forces, particularly their cavalry, from exploiting the open terrain beyond Thermopylae. This allowed the retreating Greek forces to escape and regroup, preserving their strength for future confrontations with the Persians.

Meanwhile, Xerxes began the day with making libations (liquid offerings to the gods), which was customary before important undertakings. This pause also allowed time for Hydarnes’ troops to position themselves after descending the mountain, setting the stage for a coordinated assault. Following Ephialtes’ advice, Xerxes began his advance around mid-morning.

The Persians charged at the Greek defenders, who, anticipating their final stand, had moved from behind the Phocian Wall to a wider part of the pass. The Greeks fought fiercely with their spears until these weapons were destroyed in the fight. Once their spears were shattered, they resorted to their xiphē, short swords used in close-quarter combat. The battle was intense and bloody, resulting in the deaths of two of Xerxes’ brothers, Abrocomes and Hyperanthes. King Leonidas also fell during the assault, reportedly shot down by Persian archers. A fierce struggle ensued over his body, which the Greeks finally managed to drag out and away from the crowd.

As Hydarnes and his troops entered the battle, the intensity escalated even further. The Greeks quickly withdrew to a hill behind the Phocian Wall as their position became untenable. At this point, the Thebans, who had been suspected of sympathizing with the Persians, attempted to surrender, yet some were killed before their surrender was accepted. Xerxes later branded the Theban prisoners with the royal mark, marking them as traitors to the Greek cause.

On this spot (the hill of the final stand) they (the Greeks) tried to defend themselves with their daggers if they still had them, or if not, with their hands and their teeth. The barbarians (the Persians) pelted them with missiles, some running up to face the Hellenes (the Greeks) directly and demolishing the defensive wall, and others coming to surround them on all sides.

Herodotus, c. 484-425 BC

Determined to definitively end the resistance, Xerxes ordered the destruction of part of the Phocian Wall and surrounded the hill where the last of the Greeks stood. The Persians then showered the defenders with arrows until none remained alive. This massacre was confirmed archaeologically in 1939 when Spyridon Marinatos uncovered numerous Persian bronze arrowheads on Kolonos Hill, identifying it as the likely site of the Greeks’ last stand.

The opening of the pass at Thermopylae was a strategic victory for the Persians, but it came at a substantial price. Herodotus estimates that the Persian army suffered up to 20,000 fatalities over the course of the battle. On the Greek side, modern historians estimate around 2,000 deaths, including those killed on the first two days of fighting and the total loss of Leonidas’ rearguard. Herodotus at one point mentions a figure of 4,000 Greek deaths, but this number would account for nearly every Greek soldier present at the battle if the Phocians, who were guarding the mountain path and not directly involved in the final stand, are excluded from the casualty list. Therefore, modern historians consider the number of 2,000 Greek fatalities to be more accurate.

Aftermath: Salamis, Plataea, and Mycale

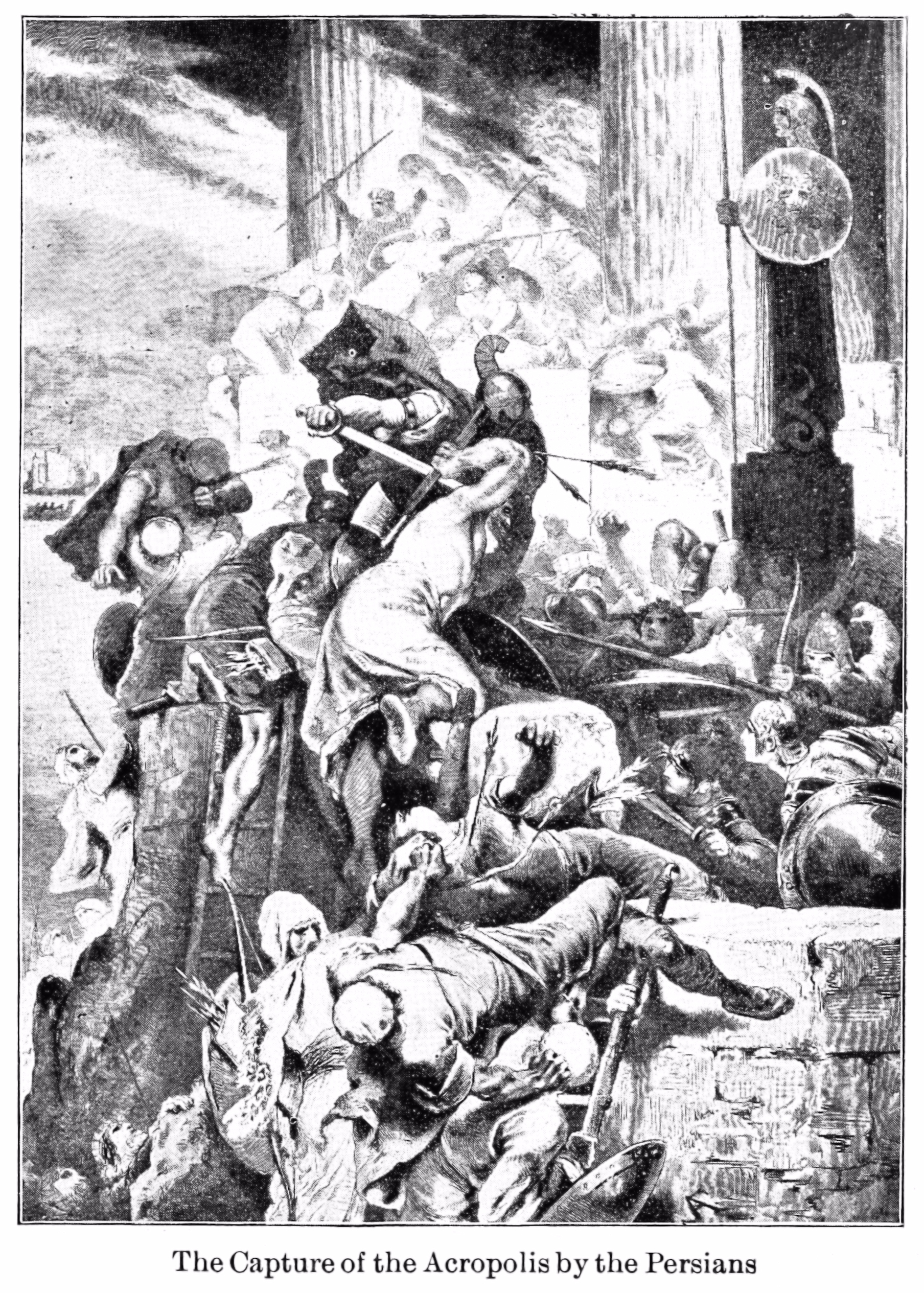

After overcoming the Greek defenses at Thermopylae, the Persian army moved southward unopposed through central Greece. They devastated the cities of Plataea and Thespiai in the region of Boeotia, both of which were important members of the Greek defensive alliance. The Persians then advanced towards Athens, which had been evacuated in anticipation of the Persian arrival. Upon reaching Athens, the Persians burned and sacked the largely deserted city.

Meanwhile, the Greeks fortified the Isthmus of Corinth, creating a formidable barrier to protect the Peloponnese. Themistocles, however, knew that more proactive measures were necessary and advocated for an aggressive naval strategy. He devised a plan to lure the Persian navy into the narrow Straits of Salamis, where the Greek triremes awaited. The subsequent Battle of Salamis was a masterful display of naval tactics. The nimble Greek ships inflicted a devastating defeat on the Persian fleet, significantly reducing Xerxes’ naval capabilities.

The severe loss at Salamis forced Xerxes to reconsider his position in Greece. Concerned about further losses and fearing for the safety of his pontoon bridge across the Hellespont, which was his supply line and retreat path back to Asia, Xerxes decided to withdraw the bulk of his army back to Asia Minor. He left Mardonius in charge of continuing the campaign in Greece.

In 479 BC, the Greek forces regrouped and prepared to face Mardonius and the remaining Persian forces. The decisive encounter took place at Plataea, where the Greeks, under the command of Spartan general Pausanias, effectively destroyed the Persian army. This battle marked a significant turning point, ending any further Persian ambitions in Greece. Almost simultaneously, the Greek navy engaged the remnants of the Persian fleet at the Battle of Mycale off the coast of Asia Minor. This battle not only further crippled the Persian naval power but also encouraged the Ionian Greek cities under Persian control to revolt, further weakening Persian influence in the region and decisively ending the Second Persian Invasion of Greece.

Conclusion

The capture of the pass at Thermopylae by the Persian forces marked a critical point in Xerxes’ invasion of Greece. However, the battle also demonstrated the effectiveness of Greek military tactics and the strategic use of terrain, as well as the high price even a victorious army must pay when facing determined and skilled defenders. The Spartan-led stand at Thermopylae became legendary, symbolizing the ultimate sacrifice for freedom and duty, and it had a significant psychological impact on both Greek and Persian forces for the remainder of the Greco-Persian Wars. The heroism and sacrifice at Thermopylae galvanized the Greek cities. Their unified response in subsequent battles, particularly Salamis and Plataea, ultimately ended the Second Persian Invasion of Greece.