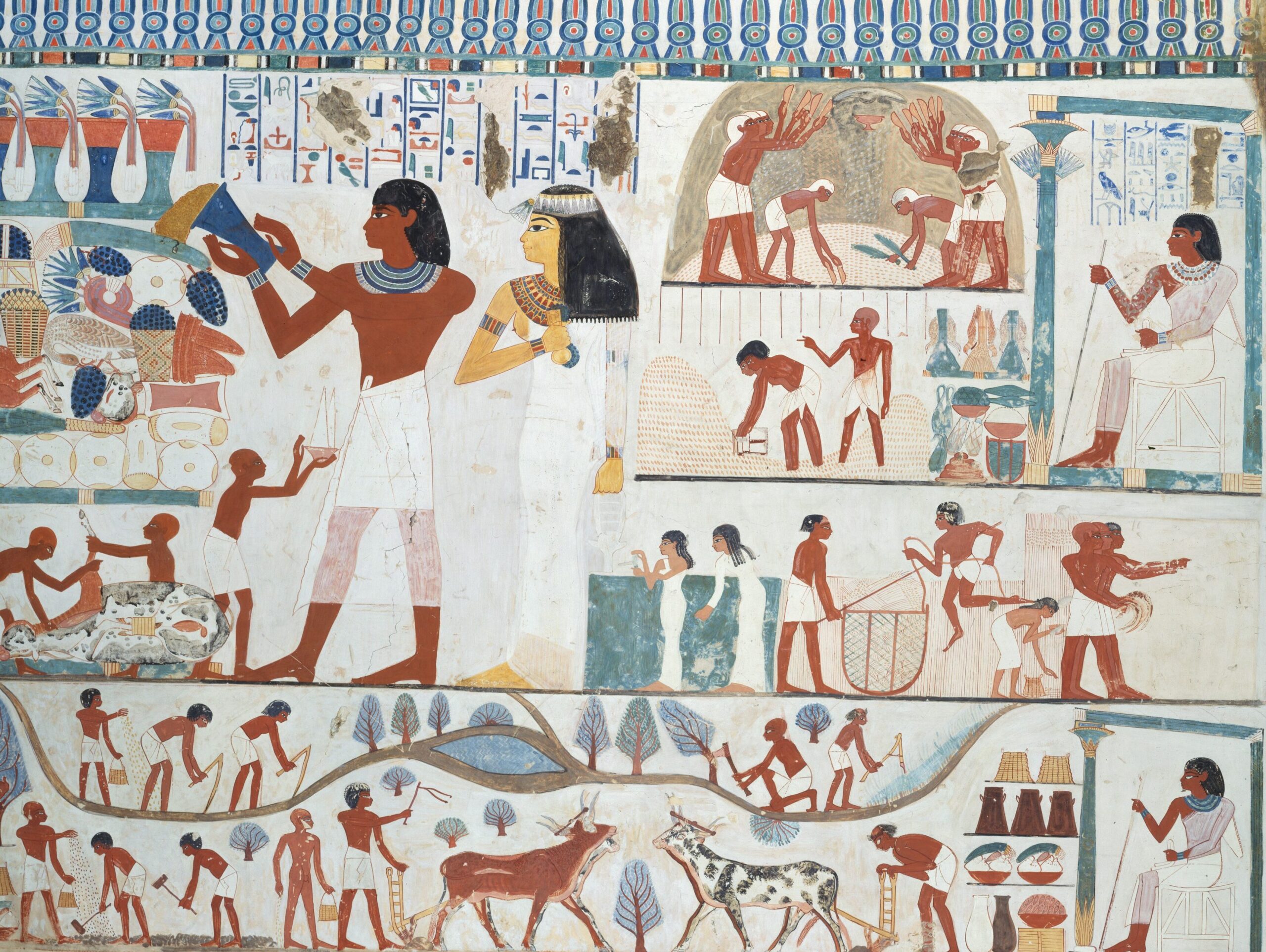

Daily life in ancient Egypt depended heavily on the rhythms of the Nile River. The lives of pharaohs and farmers alike were intertwined with the river’s annual floods, which nourished the land and dictated agricultural cycles. From the bustling marketplaces to the sacred temples, the daily routines and cultural practices of the ancient Egyptians offer a glimpse into a period of unprecedented power and prosperity.

The New Kingdom

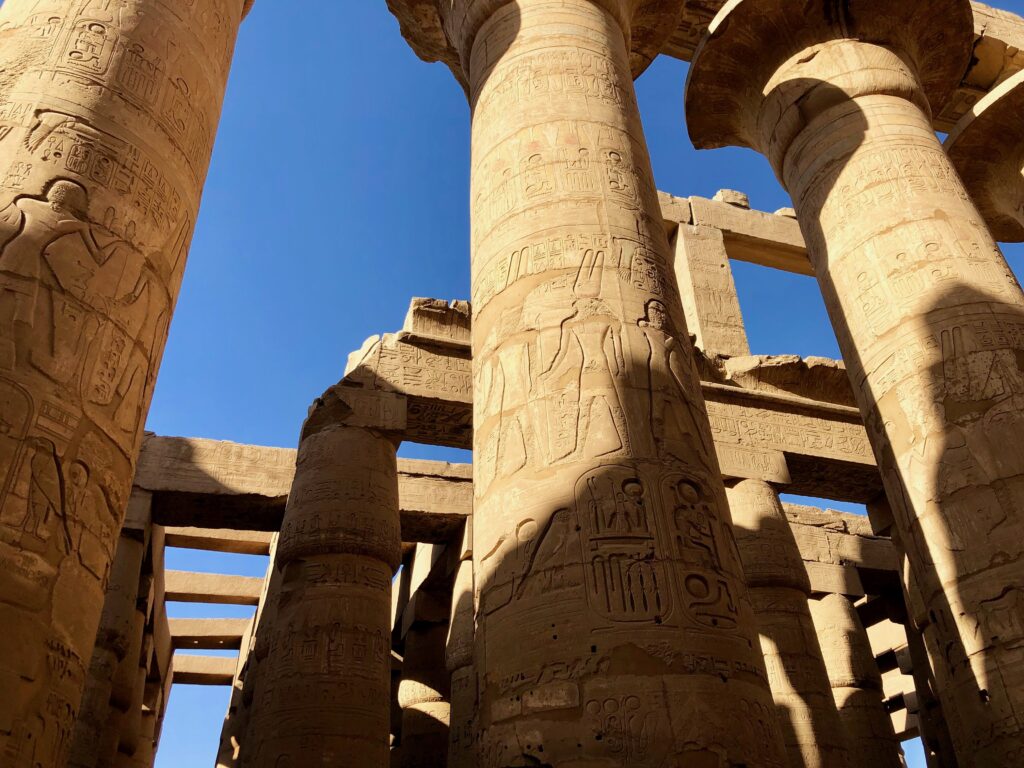

Imagine waking up to the soft glow of the rising sun over the majestic Nile River, the lifeblood of ancient Egypt. This was the daily reality for many Egyptians during the New Kingdom, an era that stretched from approximately 1550 BC to 1069 BC and is often regarded as the golden age of ancient Egypt. The New Kingdom, also known as the Egyptian Empire, began with the expulsion of the Hyksos invaders by Ahmose I, who founded the Eighteenth Dynasty, introducing a series of ambitious pharaohs who expanded Egypt’s borders through military conquests. The New Kingdom is distinguished by its architectural achievements and the construction of monumental structures. The pharaohs of this period, including Hatshepsut, Thutmose III, Amenhotep III, Akhenaten, and the famous Tutankhamun, embarked on extensive building projects that left a legacy in the form of magnificent temples and tombs, most notably in the Valley of the Kings and Karnak.

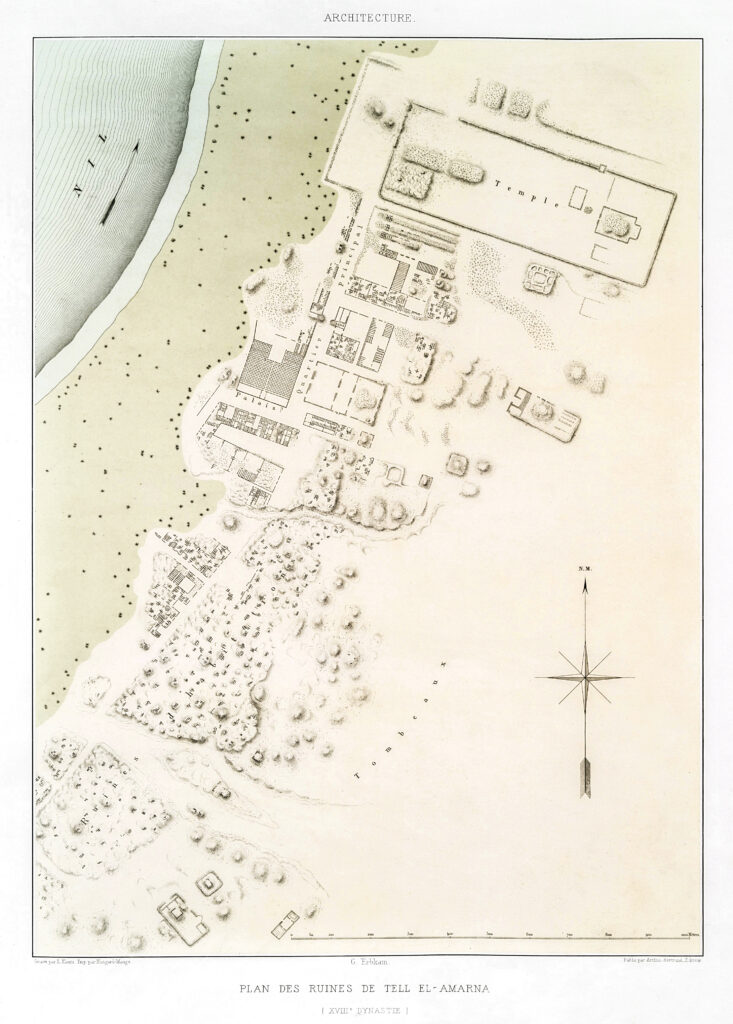

During the New Kingdom, Egypt reached the peak of its power, establishing extensive trade networks and exerting influence across the Near East, Mediterranean, and into Sub-Saharan Africa. This period is notable for the religious revolution instigated by Akhenaten, who ascended to the throne around 1353 BC. Early in his reign, Akhenaten initiated a series of dramatic changes in the religious practices of Egypt, centralizing the worship around the sun disc, Aten, which he elevated to the status of a supreme deity. This shift from the traditional Egyptian polytheistic religion to a form of monotheism was unprecedented.

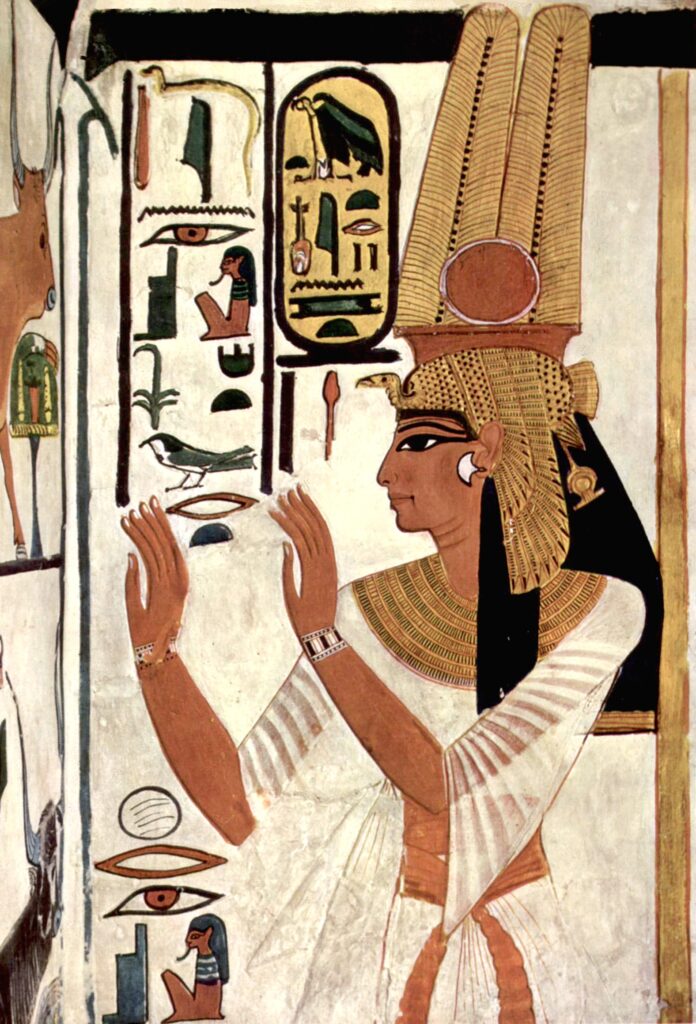

Akhenaten’s religious reforms led to the founding of Akhetaten, a new capital dedicated to Aten. The artistic style during this period also changed radically, it depicted the royal family with exaggerated and more naturalistic features, a stark departure from the idealized art of earlier dynasties. This art often showed Akhenaten and his queen, Nefertiti, in intimate family scenes under the rays of Aten, emphasizing the human aspect of the divine family.

The pharaoh’s monotheistic focus led to discontent among the priesthoods of other deities, particularly that of Amun, whose temple and priesthood were previously very influential. After Akhenaten’s death around 1336 BC, the pharaohs Smenkhkare and Neferneferuaten maintained Atenism as the main religion. Neferneferuaten’s successor, Tutankhamun, who is thought to have been Akhenaten’s son or brother, took significant steps to restore the traditional religious practices. Under guidance from advisors like Ay and Horemheb, he reverted Egypt back to polytheism. He initiated a series of restorative projects and moved the capital back to Thebes, the traditional religious center, thus re-establishing the primacy of the god Amun. During Tutankhamun’s reign, the temples and images of the old gods that had been neglected or desecrated were restored, and Atenism was definitively abandoned.

Interesting Fact

Tutankhamun’s name was originally Tutankhaten, meaning ‘living image of Aten.’ When he abandoned Akhenaten’s religious reforms and restored the traditional religious practices, he changed his name to Tutankhamun, meaning ‘living image of Amun.’

The art and culture of the New Kingdom were marked by exquisite craftsmanship and the production of some of the most iconic artifacts of ancient Egypt, including the treasures found in Tutankhamun’s tomb. The New Kingdom also saw the development of a more standardized form of the Egyptian administrative and military systems, which helped maintain and organize the empire effectively.

The period left a profound impact on the cultural and political landscape of ancient Egypt. At the same time, the era’s grand achievements often overshadow the intricacies of everyday life that was the backbone of Egyptian society. Common people, though far removed from the splendors of royal life, contributed to the state’s stability through their labor in the fields, construction projects, and artisanal crafts. Social norms and roles were clearly defined, with a complex hierarchy that influenced every aspect of personal and communal activities. Family life, too, was a fundamental aspect of Egyptian culture, with households often working together in various trades and children being taught from an early age to honor the gods and respect familial duties. Through these everyday activities, the essence of Egyptian society was preserved, ensuring the endurance of its cultural identity.

Morning Rituals and Activities

As the first light of dawn stretched over the land of Egypt, a typical morning in the New Kingdom began. In cities like Thebes, the bustling capital, and others like Memphis, families woke up in houses made of mudbrick, usually consisting of a few rooms: a main living area, a couple of smaller bedrooms, and a kitchen. The homes of the wealthy were much larger and more elaborate, often decorated with painted walls and floors tiled in clay or stone. The commoners’ floors were made of compacted earth, and roofs were constructed from wooden beams covered with mats of reeds, ideal for the hot climate. The flat roof served as an additional living space in the cooler evenings. Windows were small, placed high on the walls, and often covered with mats to keep out the sun while allowing air to circulate.

The morning air, still cool before the desert heat enveloped the day, was filled with the sounds of a city awakening. In the homes of the nobles, servants would prepare water for washing and shaving, as cleanliness was not just a matter of hygiene but a religious practice too, ensuring purity of body and spirit. Commoners would fetch their own water, often from communal wells. They washed their hands and faces, often accompanied by prayers or incantations. Both men and women typically shaved their heads to avoid lice and to stay cool in the desert heat, wearing wigs for protection against the sun.

Other morning rituals included anointing the body with oils that smelled of frankincense or myrrh, which helped protect the skin from the harsh sun. The most common garment for both men and women was the simple linen tunic or kilt, which was cool and allowed freedom of movement. Linen, made from the flax plant, was washed and bleached to a dazzling white, its purity associated with the divine. Jewelry was popular among all classes, with bracelets, earrings, and necklaces crafted from beads, metals, and semi-precious stones. Makeup, particularly kohl around the eyes, was used by both genders to ward off evil and reduce the glare of the sun.

Breakfast was generally light, consisting of bread made from emmer wheat or barley, which were staples of the Egyptian diet. This bread was often accompanied by onions, garlic, and leeks, flavors that featured heavily in the Egyptian diet. For protein, they might have eggs or slices of salted fish. Those who could afford it might also enjoy fruits like dates and figs or honey as a sweetener. Beer, which was safer to drink than the Nile water itself, was a common beverage for adults and children alike.

Work and Duties

As the sun rose, the daily activities began. Farmers headed to the fields, craftsmen to their workshops, and traders to the markets. Priests prepared for temple rituals, while women, often responsible for managing the household, engaged in tasks such as grinding grain, cooking, and weaving. Children played games or helped their parents. The structure of the day was punctuated by rituals and the acknowledgment of various deities who were believed to oversee and influence daily activities.

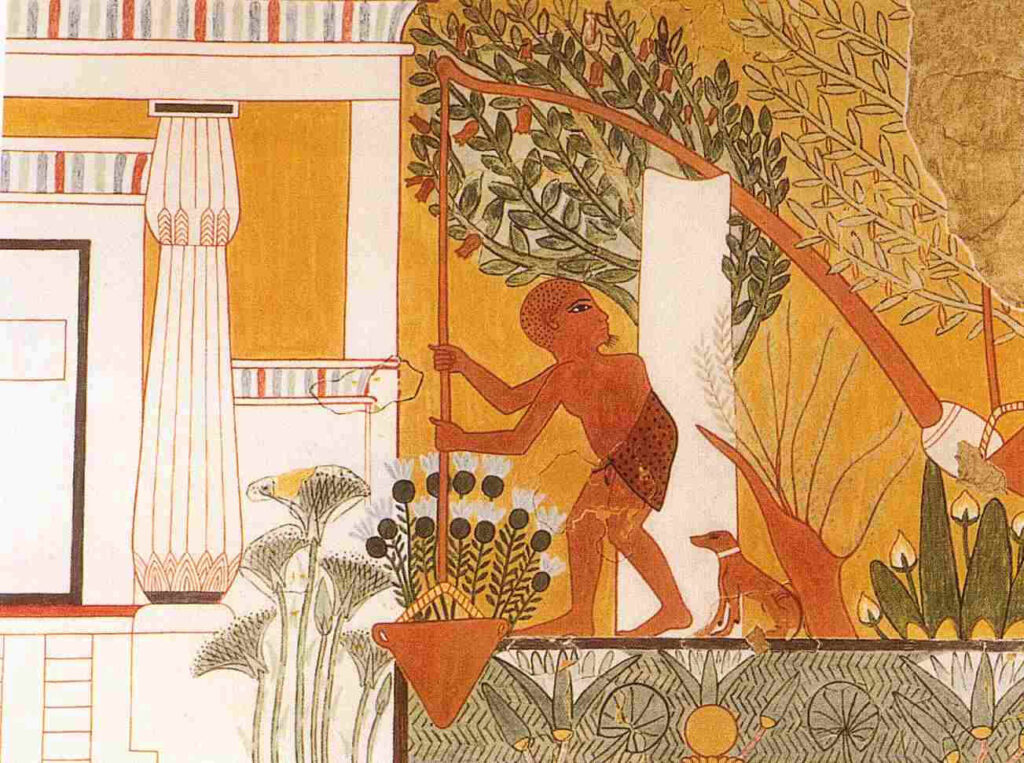

Farmers

Agriculture was the backbone of ancient Egyptian society, and most of the population was involved in farming. The fertile floodplains of the Nile provided the necessary nutrients and water to cultivate crops. Farming activities were structured around three seasons, aligned with the cycle of the Nile. Akhet, the inundation period, saw the fields submerged under water for several months, during which farmers prepared for the subsequent growing season. As the floodwaters receded during Peret, the growing season, farmers plowed the soil using wooden plows often pulled by oxen, and sowed seeds by hand. Crops such as wheat, barley, and flax were predominant, along with various vegetables like onions, leeks, and garlic. Irrigation during this period was crucial, involving the use of a shaduf to regulate the moisture level of crops. Shemu, the harvest season, involved intense activities where laborers reaped the crops with sickles, followed by threshing and winnowing to separate and clean the grain, which was then stored or distributed. The harvests were highly organized community efforts, overseen by officials to ensure that a portion was set aside as tax for the state or local temples.

In terms of labor, the agricultural landscape was comprised of several types of farmers each with specific roles. Most were state peasants who worked on land owned by the state or temples, paying taxes in the form of produce and labor. Tenant farmers, who rented land from landowners or temples, had more control over their produce but still owed rent in the form of crops. Additionally, wealthier individuals, such as nobles and high-ranking officials, owned large estates and employed farmers to cultivate their land, overseeing the larger management while daily farming tasks were carried out by employed laborers.

Farmers utilized a variety of tools made primarily from wood and stone, including simple but effective plows for turning the soil and sickles with flint blades for cutting grain. The success of agriculture in ancient Egypt was deeply dependent on the coordinated use of the Nile’s waters through complex irrigation systems and the communal effort of various farmers. This effective agricultural system allowed for the flourishing of construction, trade, and arts throughout the empire because it supported a population that could engage in activities beyond sustenance farming.

Craftsmen

Craftsmen in the New Kingdom were highly skilled and specialized in various crafts. They played a vital role in society, creating everything from everyday household items to exquisite artifacts intended for the tombs of pharaohs. Craftsmen typically worked in specific areas designated for their particular trades, often organized in workshops and guild-like structures that could be state-sponsored or privately managed. The most famous example of a state-sponsored community of craftsmen is the village of Deir el-Medina, located near the Valley of the Kings. This village housed the workers responsible for constructing and decorating the royal tombs. Records from the village, including ostraca (pottery shards used as writing surfaces) and papyri, provide details about their work schedules, events in the village, and personal letters. These documents reveal that the workers often operated in teams and followed a rotational system, with periods of work followed by days off, during which they could attend to their personal affairs and family needs. The village’s extensive archaeological remains, including the well-preserved tombs of the workers themselves, adorned with beautiful decorations and inscriptions, provide a glimpse into the lives of the people behind some of Egypt’s most magnificent monuments.

The variety of crafts practiced in the New Kingdom was extensive. Stone carvers and sculptors were essential for the creation of statues, stelae, and temple reliefs. Using hard stones like granite and softer stones like limestone, these craftsmen would translate the pharaohs’ and gods’ representations into stone, which were then displayed in temples or used as tomb decorations. Carpenters crafted furniture, chariots, and tools, using both local and imported wood.

Metalworkers were another crucial group, handling materials like gold, copper, bronze, and iron. They made tools, weapons, jewelry, and amulets. Goldsmiths, in particular, were highly regarded for their skills in making jewelry adorned with semi-precious stones and intricate designs, reflecting wealth and religious beliefs. Potters used the rich Nile clay to make pottery used in both daily life and ritual practices.

Another significant craft was that of the textile makers, who produced linen from flax plants grown along the Nile. Textiles were a major part of the Egyptian economy, used in everything from clothing to barter goods. Weavers were skilled at producing fine linen that was used for the mummification process and by the living for garments, with the quality of the fabric often reflecting the social status of the wearer.

Craftsmen generally worked under the supervision of overseers, who ensured that their output met the standards required by their patrons, which included the state, temples, and wealthy private individuals. Many craftsmen spent their lives perfecting their skills, which were passed down through generations.

Religious Officials

Priests were primarily responsible for maintaining the gods’ cults, ensuring that the deities were appropriately appeased through rituals and offerings, which they believed were essential for maintaining Ma’at: the divine order and balance of the universe. This role required them to perform daily rites in the temples, which included cleansing the sanctuary and offering food and clothing to the gods’ statues. These statues were believed to house the essence of the deities, and the care provided by the priests was thought to sustain these gods and invoke their favor on behalf of the Egyptian people.

The most significant temples had a hierarchy of priests with various duties and levels of access to the inner sanctums. At the top was the High Priest, often a close advisor to the pharaoh and involved in state matters. Below him were the priests specialized in specific gods or aspects of the temple service, including ‘lector priests’ who read sacred texts during rituals, ‘wab’ priests responsible for purification ceremonies, and ‘horologist priests’ who kept the ritual calendar.

Temples were not just religious centers but also hubs of economic activity and learning. They owned vast tracts of land, managed by priests who oversaw agricultural production and the activities of the laborers. This economic power made the priesthood one of the wealthiest and most influential classes in the New Kingdom.

Additionally, temples were centers of learning and education. Priests were often scribes, and they were responsible for the education of young novices in various subjects including theology, medicine, and mathematics, essential for maintaining and transmitting cultural and religious knowledge. This educational role was crucial, as literacy and learning were concentrated among the elite, of which priests were key members. They also played a vital role in major festivals and public ceremonies, which were essential for reinforcing the social and political order. Festivals allowed ordinary Egyptians to interact with the divine, as statues of gods were paraded from the temples into the community.

Government Officials

The structure of the Egyptian administration was highly hierarchical and centralized, with the pharaoh at the top as the supreme ruler and divine intermediary. Directly below the pharaoh were the viziers, who served as the prime ministers. The viziers were responsible for overseeing all aspects of state administration, including the legal system, the treasury, and large construction projects. They were the chief coordinators for the various departments of state and were often key advisors to the pharaoh.

Further down the hierarchy were the nomarchs, or provincial governors, who managed the nomes (provinces) into which Egypt was divided. Their duties were akin to those of modern-day governors, involving the collection of taxes, supervision of local agriculture and water management, and maintaining local law and order. They were crucial in implementing the central government’s policies at the local level and ensuring that the provinces remained loyal to the pharaoh.

Additionally, there were numerous specialized officials such as treasurers, who managed the kingdom’s wealth, overseers of granaries, who were responsible for the storage and distribution of grain, and army commanders, who led military campaigns and maintained defense systems. These officials were typically drawn from the upper echelons of society and often served in their roles for life, passing their positions on to their descendants, thus maintaining a stable and experienced administration.

Scribes were the backbone of the Egyptian bureaucracy and were indispensable in the administration of the state. Educated in scribal schools, usually attached to temples or palace complexes, scribes learned to read and write hieroglyphic and hieratic scripts, mathematics, and various administrative and legal codes. This education enabled them to perform a wide range of duties, from recording court proceedings and tallying tax contributions to documenting the outcome of battles and diplomatic missions. Scribes worked everywhere, from government offices and royal courts to military outposts and construction sites. They were employed to keep records that were crucial for the administration, such as census data, land surveys, and religious offerings.

The interplay between government officials and scribes was fundamental to maintaining order and efficiency within the New Kingdom. Officials relied on scribes to document and communicate decisions and to keep accurate records that were vital for administration, while scribes depended on officials for their authority and the implementation of policies. Together, they formed a network that underpinned the political and economic structures of the kingdom, facilitating the pharaoh’s rule over the vast empire.

Midday Meals and Social Life

As the scorching midday sun reached its peak, the ancient Egyptians took a well-deserved break to recharge and escape the relentless heat. Midday meals were typically more substantial than breakfast. The diet might include lentils, chickpeas, and cucumbers, along with preserved fish or small amounts of meat for those who could afford it. Bread remained a constant, often dipped in honey or fruit preserves to add flavor. Meals were commonly washed down with more beer or, for the affluent, wine made from grapes grown in the Nile Delta.

The midday break was also a prime time for social interactions. As the heat forced a pause in labor, people gathered in cooler spaces, often marketplaces, which became lively centers of community life. These markets were not only for buying and selling goods but also for the exchange of news, stories, and gossip. Craftsmen, who needed supplies for their crafts, might use this time to barter for materials. Meanwhile, nobles and officials could often be seen managing or overseeing the distribution of resources like grain. The marketplace functioned much like an agora in ancient Greek cities, a central hub for both commerce and social interaction.

After the midday break, work would typically resume and last until the late afternoon. The duration of the workday was not just a matter of labor efficiency but also of practicality, considering the heat and the natural light available. Ending the workday at or before sunset allowed workers to return to their homes with enough light to safely navigate their way, attend to personal and family needs, and engage in social activities within their community.

Leisure and Culture

The timing of leisure activities in ancient Egypt was largely dictated by the agricultural calendar. During Akhet (inundation period), farmers had more free time for leisure activities, while Peret (growing season) and Shemu (harvest season) required more intensive labor, reducing the available time for leisure. Additionally, the daily work schedule typically included breaks during the hottest part of the day, providing opportunities for rest and lighter activities.

Leisure time was often spent engaging in various forms of entertainment that ranged from sports to board games. Popular sports included fishing and hunting, which were not only recreational but also practical in terms of providing food. Archery and swimming were also common, along with a form of wrestling and stick fighting, which were often depicted in tomb paintings and might have been spectator sports as well.

Board games were another popular pastime, with Senet being the most famous among them. Senet, which means ‘passing’, had religious connotations and was believed to reflect the journey of the soul into the afterlife. This game was played on a board with thirty squares, arranged in rows of ten, and involved two players moving pieces according to the roll of dice or throwing sticks. The game was so beloved that it was often included in the grave goods of the deceased.

Music and dance were also central to Egyptian leisure, enjoyed by people across all classes. Music was played on instruments like the lyre, harp, and flute, while dancers entertained the crowds at both public festivals and private banquets. These performances also had ritualistic and ceremonial importance, frequently occurring during religious festivals and funerary rites.

Religious festivals were perhaps the most significant cultural activities in the New Kingdom, with the average Egyptian participating actively. These festivals provided an opportunity for the community to come together, transcending social classes to some extent. While daily life was rigorously structured, festivals were occasions where ordinary people could engage in celebrations alongside the nobility and priesthood. The Beautiful Festival of the Valley, for instance, saw people from all walks of life gathering to honor their ancestors. During the festival, the sacred barque (a ceremonial boat) carrying the statue of Amun would be brought out from the sanctuary of Karnak and carried across the Nile to the West Bank, where the major royal and private tombs were located. This journey symbolically represented the daily travel of the sun, which died in the west each evening and was reborn in the east each morning.

Evening Routines

As the sun set, the heat of the Egyptian day would dissipate, and people would take advantage of the cooler temperatures. Farmers and craftsmen would return home from their fields and workshops, while officials and priests concluded their administrative and ritual duties. This was a time for personal hygiene and relaxation. People typically bathed after the day’s work, using water from the Nile, and took care of their appearance by reapplying oils and perfumes.

Dinner was the principal meal of the day and involved more elaborate preparations. Families gathered to share dishes made from vegetables, lentils, and meats, often cooked in stews to enhance flavors and conserve cooking resources. Evenings were also a time for socializing. Families and friends gathered to share the events of the day, and neighborhoods came alive with the sounds of conversation and music. Storytelling was a popular evening pastime, with tales of gods, heroes, and everyday life being both entertainment and moral education. Additionally, the clear desert nights provided a perfect backdrop for stargazing. The stars were thought to influence the fate of Egypt and were integral in the mythology and cosmology of the New Kingdom.

Before bed, families cleaned and prepared their sleeping areas. Homes were secured, and prayers might be offered to household gods for protection during the night. Small shrines in homes were common, where family members might offer prayers and incense.

Conclusion

In ancient Egypt, the rhythm of daily life was a delicate balance between labor, devotion, and community engagement, reflecting a society that was both complex and deeply interconnected. The structured work activities reflected not only an organized approach to agriculture, crafts, and administration but also an understanding of the natural rhythms of the Nile and the seasonal cycles that dictated economic and social life.

Leisure activities, including games, sports, and musical entertainment, played a crucial role in maintaining social cohesion. The importance of religious and cultural practices was evident in every part of their day, from the prayers at dawn to the protective rituals at night. Evening routines brought families and communities together, ensuring that the values, stories, and traditions of the Egyptians were continually celebrated and preserved.

The ancient Egyptians’ ability to balance between hard work and community interaction helped to sustain their civilization through centuries, allowing them to achieve remarkable feats in construction, arts, and culture that continue to fascinate the world today.